Architects getting automated?

Daniel Davis writes that he doesn’t think that architects can be automated. I know Daniel a little bit, he’s very switched on. I think he watered down the conclusion to that article to please the audience. Readers of Architect magazine aren’t likely to be receptive to being told that they are a few years away from being automated out of existence. I think he took it as close to that as he could get away with.

Daniel links to a fantastic paper: The Future Of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs To Computerisation? I feel like it’d be a disservice not to sumarise it for you.

It starts with a fascinating history of how automation has affected industry, from Adam Smith’s pin makers and how the Luddites weren’t so into looms. Then it goes into what is and isn’t automatable. (All quotes are from that paper, refs are also from within the paper.)

Historically, computerisation has largely been confined to manual and cognitive routine tasks involving explicit rule based activities (Autor and Dorn, 2013; Goos, et al., 2009). Following recent technological advances, however, computerisation is now spreading to domains commonly defined as non-routine.

There’s a little bit of discussion of the limitations of the current wetware fulfilling the role

Humans, in contrast, must fulfill a range of tasks unrelated to their occupation, such as sleeping, necessitating occasional sacrifices in their occupational performance (Kahneman, et al., 1982).

And then they knock over a whole series of sacred cows that “just can never be automated” (clutch the pearls!)1.

Hence, while technological progress throughout economic history has largely been confined to the mechanisation of manual tasks, requiring physical labour, technological progress in the twenty-first century can be expected to contribute to a wide range of cognitive tasks, which, until now, have largely remained a human domain…Nonetheless, the trend is clear: computers increasingly challenge human labour in a wide range of cognitive tasks (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2011).

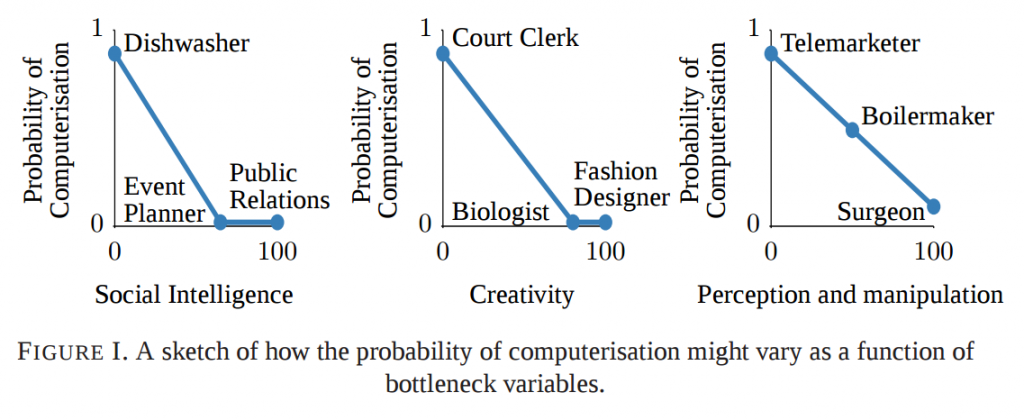

All of that is the preamble to the novel contribution–a reformulation of a method of calculating a job’s automatability. The main factors affecting a job’s chances are the summed prevalence of “perception2 and manipulation tasks, creative intelligence tasks, and and social intelligence tasks”.

If you are a bit allergic to mathematical notation and very-hard-statistics then you can skip section 4 which is the how, and move right onto the what happens next part.

If you are a bit allergic to mathematical notation and very-hard-statistics then you can skip section 4 which is the how, and move right onto the what happens next part.

Because we’re all impatient, and keen to know how the story ends…

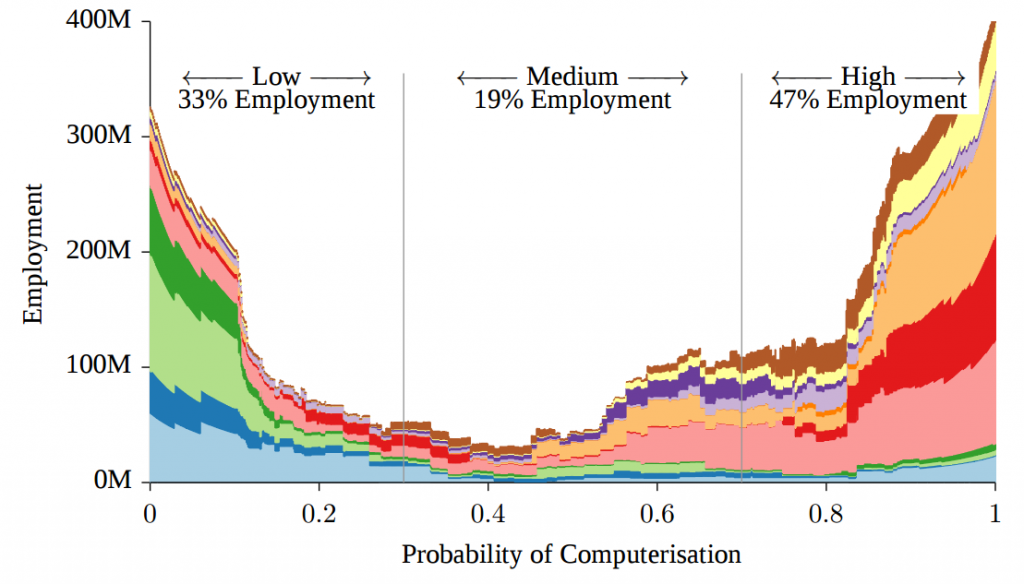

We’re (architects) in the one of the blue bands right on the left–in the low risk area. (The little square is a legend.)

The way it plays out is that the people in the high area should be really worried. Those in medium are protected by a bottleneck that will eventually be overcome. Those of us in low can feel safe for a while.

1.8% chance of replacement Architects, Except Landscape and Naval

If you want to know how the story ends you can read the whole paper. For now, back to my rant about how I think this will play out in architecture.

I recently read Nick Bostrom’s latest book, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. He talks about how AI will some day reach human-level general-intelligence. I’m a materialist, and I agree with him. I don’t see anything special about our neural machinery that will prevent it3,4.

If we agree that human-level artificial general intelligence (AGI) is possible5 then it follows that most, if not all tasks that we classify as knowledge work can be automated. Some might not eventually get automated. Perhaps we value the knowledge that a human artisan designed our poster. Just as we like that one crafted our beer or our table.

The discussion at hand is really about the period between right now, with the technology that we have access to, and the birth of the first serious AGIs6.

I think that Daniel dodges the meat of the question by not defining what he means by “the architect”. Whenever I attempt to be profound I need to qualify it so much that it no longer sounds convincing. Imagine me saying the next sentence in my profound tone of voice. Professions don’t often get automated, tasks do. Whole professions get automated when the tasks contained within them are all automated. Until that point the remaining people in the profession are busily patting themselves on the back for being so efficient!

I’d imagine that if you’d asked someone 40 years ago what part of their job was going to be replaced by a machine they wouldn’t have picked drawing sections7. There are lots of things that we once did as time consuming manual processes. The effort to make a copies of drawings often kept someone employed full time. I’m not best placed to talk about what has changed since the good old days, but my feeling is that it’s a lot. Each of those steps towards making designing buildings more efficient changed people’s lives. It manifested itself in teams getting smaller and time-scales getting shorter. It also meant that we did more. We do photorealistic renders, we do more comprehensive documentation8.

The trend seems to be that the non-design parts of getting a building communicated to whoever–or soon when it’s robots, _what_ever–is building it are being removed. Without strong AGI the parts that need the most ‘creativity’9 will still be performed by humans. They will be the only parts though. As I’ve said elsewhere, delegating is analogous to programming. If it’s possible to delegate a task then it’s a good bet that you can automate it.

Architecture will be cut right to the core. Let’s assume that automation doesn’t improve speed (which is will) for the sake of this point. A company the size of the one I work at (about 250 people) could maintain its output at the level it has now with about 30 people10.

I’d imagine that you are feeling pretty glum now. Odds are that you aren’t in that magical group of 30 (30 people out of 240 or 1 in 8). That’s not the most cheerful statistic.

I don’t think that a world where 30 people, augmented by a bunch of whizzy technology, will replace all the people who currently do this job. It won’t be good enough! As the required effort to produce drops, clients expect more.

Let’s use making websites in 1995 compared to today as an example. In 1995 it took a big team of people working very hard to make quite very bad (by today’s standards) websites. Process and tooling has improved enormously in the last 20 years. This has meant that a lot of making websites is automated. An example of that is WordPress. That’s the software that allows me to write this and you to read it11. I’m sitting on my sofa and I haven’t paid a team of professionals to get these words in front of your eyes. If that’s the case (anyone can get stuff on the internet) then how come there’s this “tech sector boom” that everyone keeps harping on about?

It’s the quality stupid! Your team of people isn’t focused on getting words to appear on screens any more. Some people are making sure that your site doesn’t crash when a billion people want to watch a chubby Korean pop star. Another team might be doing studies of people’s habits in their homes so that your product/site can serve their needs more perfectly12. There will be people looking at all kinds of stuff, because their competitors are.

Unwinding the metaphor, we aren’t a wordpress organisation13, we are the bespoke, high end of things. We’ll have that 30 people doing what we do now (after a fashion) but we’ll have people doing all kinds of stuff that we don’t do now. Anthropologists, psychologists, physicists, people running experiments, people developing apps that run the building and make it react to it’s occupants. All those people will be adding more value to the end result.

Hopefully enough value to push back the date of the profession’s disappearance a long time. But once the strong AGI turns up it’s all over!

-

A question that’s been nagging at me is brought up by: “workers will reallocate their labour supply according to their comparative advantage as in Roy (1951). With expanding computational capabilities, resulting from technological advances, and a falling market price of computing, workers in susceptible tasks will thus reallocate to nonsusceptible tasks.” That was true in 1951, it’s probably still true in 2015. There are two possible dis-equilibriums. At some point the volume of workers displaced from susceptible tasks may exceed the number of roles in nonsusceptible tasks. As a general fan of creative destruction I think that this is probably unlikely. The other is a dynamic failure. If the rate at which workers are displaced exceeds the rate at which they can be re-placed then there will be trouble! ↩

-

The paper is pretty into human superiority in visual processing, but it was written in 2013, google has been making big steps in visual processing. Also, check out their trippy deep dream stuff. ↩

-

He goes on to talk about the intelligence explosion that follows and how to make sure that we don’t end up as a footnote in history. If you want to read some really serious and hard, but pertinent and useful philosophy, then this is a good bet! If you just want a taste of what it’s about then you can listen to an interview with him. ↩

-

Robin Hanson thinks that emulations of human brains will happen even sooner, but Nick Bostrom and Anders Sandberg think that it’ll be about 20 years. 20 years is a magic number in AI, it’s always 20 years away, but even so, that’s still pretty soon! If they are right that means that the whole of this story is going to play out in the next two decades! ↩

-

If you don’t agree, I’d love to have a chat. I’ve never understood anyone’s objections so I want to try! Even if I don’t agree, understanding your objection would be great. ↩

-

An AGI needn’t be human level, in fact we have AGIs right now that outclass a mosquito. Last time I checked they were up to slug level, so by now they might even be up to beetle smarts! ↩

-

I’ll have to ask Graham when I see him at the next commons meeting for his thoughts on the matter ↩

-

I’ll leave people’s thoughts on how much we should be documenting out of this for the moment. I’m in the more information camp in case you wondered. ↩

-

Whatever that actually means! ↩

-

I think that it is conservative! I’ve also completely pulled this number out of the air. My reasoning goes: The majority of the high level design work is done by a small number of people. Everyone else is exploring ideas, making documents or coordinating internally or with other parties. If the work done by the “everyone else” group is automated, and a chunk of the work done by that small group is also automated then they’ll have no trouble maintaining current output! ↩

-

This post was intially written in wordpress, but now the back end of this blog is actually Jekyll. ↩

-

By perfectly, you can read that as “your product works better so more people pay to use it” or however it best suits your version of reality. ↩

-

Lots of architects are though! They’ll be toast when the automation allows people to circumvent them. Those who provide a service to people who need them, but would rather not be bothered with the frustration. People who need to submit a DA for their shed. Maybe even people throwing up generic industrial estates. I optimistically think that–as the rest of my scenario unfolds–performance regs will make it hard to cookie cutter buildings. ↩