codifying architecture

This is another piece I wrote for my design studio, it’s got a missing reference so if anyone knows the answer then I’ll buy you a mars bar.

it ends on a bit of a grumpy note, but i could have just carried on ranting for hours.

Codifying architecture

The goal of this assignment is to consider and critically examine some of the ways in which Architecture and Design are ‘codified’, and explore how they are used to either obscure or explain design. Examples to look at might be building codes, proportional systems, Christopher Alexander’s theories, Feng Shui, Vastu Shastra, Gaudi… etc. Read 4 or so of the texts below, and use them to compare, and contrast some different ways architecture and building is ‘codified’. Use this to reflect on how society and its institutions and power structures presently code built form.

In a universe of almost infinite complexity, the human capacity for understanding would be totally overwhelmed without some sort of system of generalisation that allowed us to understand things at a more global level than just a collection of charged particles in a lump.

The foundations of language must have been a way of explaining things that an individual found interesting to others. Without knowing anything about linguistic anthropology, I would imagine that early language was based on sounds that conveyed emotions and a lot of pointing. The development of nouns must have required a new level of cooperation to agree on a uniform set of words to describe objects. It’s almost impossible to think of an example of a statement that consists entirely of emotions as the most tempting ones always include a noun – scary place, big rock, and so on. These seem simple to us as we all agree on what a place is, and what rock is, even if the boundaries of our definition are blurred, there is enough overlap for us to communicate with each other without being misunderstood too often.

The codification of knowledge in order to create built form was probably implicitly used before society really noticed. In Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Alexander (1964) discusses the Mousgoum people from Cameroon. Their way of building houses is passed fluidly through the generations by imitation, and collaboration on others houses before building ones own. In this way, the codification is embedded in the culture, and is never made explicit.

The codification of knowledge in order to create built form was probably implicitly used before society really noticed. In Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Alexander (1964) discusses the Mousgoum people from Cameroon. Their way of building houses is passed fluidly through the generations by imitation, and collaboration on others houses before building ones own. In this way, the codification is embedded in the culture, and is never made explicit.

As the rate of cultural change has accelerated, there is no longer time to ‘learn by doing’ as by the time we have finished one project (or in the case of most architecture these days, even started it) it is out of date, and we must assimilate a new range of technology and thinking into the next project. This has required that design becomes a separate activity to building. As a result of this, the design must be communicated in some way from the ‘thinker’ to the ‘doer’. I’ll leave the discussions that arise from the implications of segregating the acts of thinking and doing for another time, but the important thing is that the two parties have an unambiguous method of communication, a language that they can both understand.

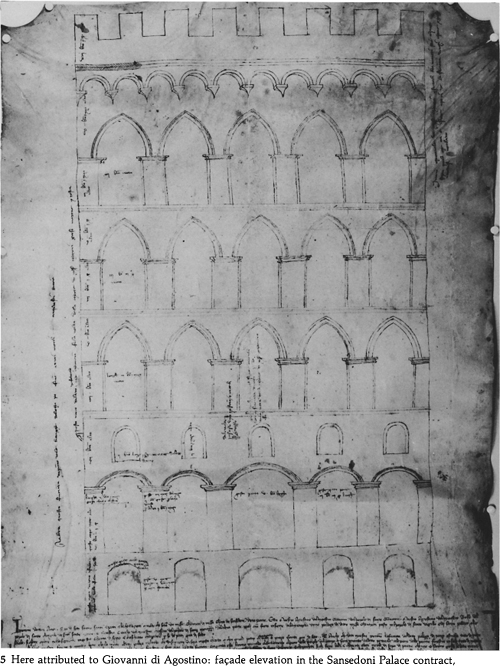

There is a long history of communicating design intents. Initially the communication was on site, I presume that there must have been verbal project management of very early buildings, where one person was leading the project and others took orders, through to the metal templates made by masons for controlling the building of cathedrals. Toker (1985) refers to several examples of master builders supervising large numbers of projects simultaneously. It is not clear what the methods used were, but it was clearly not a ‘hands on’ approach.

[insert the renaissance dude who first did an architecture project entirely remotely] was probably the first to design a project entirely remotely. This coincided with Brunelleschi’s formalisation of perspective drawing, and allowed for designers to be totally separated from builders.

In the modern western world, the ‘drawing package’ as a discrete description of the entire finished product is a well established idea. The codification into line drawings of building designs has been polished over the last 600 years and is adequate for most uses.

Attempts to replace the paper drawing with 3d models have met with limited success. Partly because of the massive inertia of the paper based system, and partly for the same reason that design emerged as a discipline in the first place. The paper based system has evolved over an incredibly long time, and the computer model as a final representation of a design has only been seriously considered for the last couple of decades.

Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) are heralded as the solution to the problem of moving away from paper drawings into an intelligent model of the end product. The theory that a building can be represented by a logical, object based structure is sound, but the real advantage heralded by the model is that it gives different disciplines a way of interacting in an unambiguous way. However at the current level of development of the technology, the level of engagement with the technicalities of the implementation, and require that everyone’s domain of understanding overlap to a huge degree.

This falls foul of the same problems that Esperanto did. In trying to be a language that all people could use to communicate, it failed to take into account that communication is far more than the act of transfer of data encoded as language. Even if both parties are encoding and decoding using the same language and meanings, the amount that is lost through the non verbal aspects of language, and also the subtleties of word use in particular contexts. This is why face to face contact is so much more effective at conveying information than an email.

The distinction between data and understanding is really the issue here. “Data is raw. It simply exists and has no significance beyond its existence” (Bellinger et al). Data is what we exchange when we pass drawings, computer files, or even speak to each other, however ‘understanding’ requires us to interpret the data and build a set of beliefs based on it. This really means that we only need to understand enough of each other’s view of the world to get the job done; any more is just a bonus.

Universal ways of representation like the IFCs also call into question the value of the meta-value of the codification of architecture. The value of ‘thinking through doing’ that can be performed by doing certain types of activities is diminished when it is considered inefficient to do work other than slavishly attending to the needs of the building model.

Bellinger, G., D. Castro, and A. Mills. (2000). “Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom,” available at http://www.systems-thinking.org/dikw/dikw.htm</address>

Toker, F (1985)”Gothic Architecture by Remote Control: An Illustrated Building Contract of 1340”

The Art Bulletin, Vol. 67, No. 1, (Mar., 1985), pp. 67-95</address>