space hacking

As my 200th post I was going to write some stuff about ethics and dolphins, but Wikipedia has already done the lions share of the work so it’s left me feeling rather unnecessary. I was considering this as I came up the escalator at Town Hall station today (my legs are tired from a long walk yesterday so I didn’t feel like walking in). I was on the right and walking up the steps behind all the other karoshi who were doing the same, trudging hurriedly towards our desks. When I got to the top the girl in front of me stopped, did a sharp right turn and headed off to the ticket barriers; this made me stop and presumably made the person behind me stop. This sort of blockage never really stops anything, but acts more as a constriction. This sort of constriction seems to slow down the flow of people through the station, which reduces the station’s efficiency. (If you assume that the job of a train station is it’s obvious one, i.e. to move people about quickly, get them from where they are to where they want to be by making the journey from their entry point to exit point as time-short/distance-short as possible.)

This all felt like a bit of an epiphany, a keystone that made a lot of things that I’ve been thinking about recently make sense. There must be small things that we can do that make buildings ‘better’. Defining better is an extremely fraught enterprise, but we can make a start along the axes of more profitable?, more enjoyable?, more healthy?, and add more subtlety as we go along. This feels like hacking, not making grand gestures that are based on what we think we know, but tinkering until things work a bit better, gradually finding ways to make spaces that ‘work’ better than they do now.

This all seems to merge my recent interest in cognitive biases, behavioural economics, overconfidence in designers, making measurements of behaviour of people in spaces and Hanson’s Homo Hypocritus (to name a few of the things that I’ve been looking at) with a project that I did with Angela Woda when I was studying at RMIT under Barnaby Bennet and Mark Burry which after much "fuckwittery" (Mark’s words) ended up being about improving transport efficiency by changing user behaviour.

The general thesis was that by making the transport system more efficient that the need to build new stations would be alleviated. Reliance on public transport increases with an increasingly urbanised population, and new stations are expensive, and often not very useful1 for improving the efficiency of the system. we proposed that they best way to improve the efficiency of a train station was to find a way to encourage the passengers to behave in a way that maximised their efficiency, and minimised their obstruction of each other2.

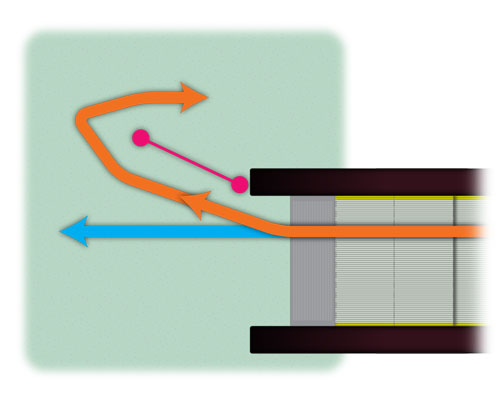

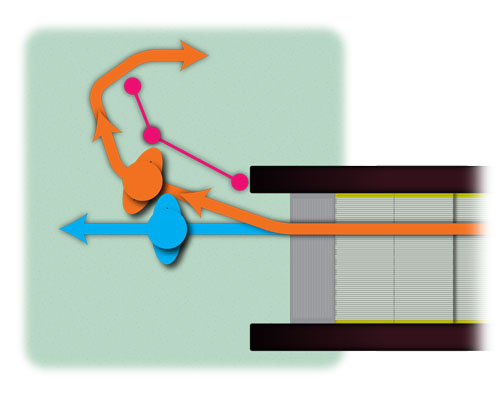

The experiment that popped into my head as my path leading from the escalator to the concourse was blocked by the turning girl was very simple; what if there was a barrier at the top of the escalator?

My hypothesis is that there is a time penalty associated with sharp turn angles, and that therefore some sort of barrier would allow for a greater flow of passengers. More specifically, the mixture of turning and non-turning passengers slows everyone down to turning speed.

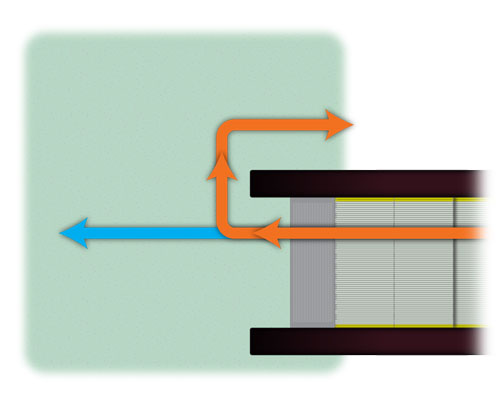

There are two possible directions from the top of the escalator, so at the moment there are two types of people when it comes to getting off the escalator3. The other main problem is people who stand on the right, apparently unaware of the social norm that encourages them to stand on the left and walk on the right; signage and loud huffing seems to solve this in London, but I think that people are too laid back/conservative to huff or use signs here in Sydney.

If the streams were to be split gently rather than in the abrupt manner that they are now then they would allow more people to escape the escalator before they clashed at the turn point. This would probably only delay the blockage, but the increased turn radius might make it less damaging.

From drawing these diagrams I’ve come to the opinion that probably the important things in this are going to be

- The amount of separation between the streams before the 'turners' start to slow down. They need to be able to walk past each other before they start to act differently.

- The radius of their turn, sharper turns are likely to result in more of a slow-down.

- Being able to prevent people from standing on the right and thereby impeding the flow of passengers.

I think that actually performing this experiment would be pretty straight forward, the audience passing the top of the escalator can easily be tracked with a thermitrak camera, and then some method of comparing actual flow with theoretical maximum flow could be developed. The conditions could be varied quite simply with some sort of heavy barrier. Lots of variations and lots of data follows!

What a massive rant! What is the point of all that? I know I’ve probably run into the tl;dr. realm, but I felt that I needed to get at least one tractable example of what I’ve been thinking about. Let’s see if any of this comes to fruition over the next few months/years!

(this is probably going to evolve as we go along!)

The Space Hijackers in London do this sort of thing, but from a more activist perspective. I bet that there is loads of work on this sort of thing already just waiting to be uncovered if I actually started looking!

-

I’d imagine that the most efficient system would be a bit like a chair lift where there is a continuous supply of transport from A, where people are, to B, where they want to go. This isn’t particularly good, as it would mean that there could only be 2 places on the system, and it is highly unrealistic. That said, I’d imagine that Andrew could bring some lattice theory to bear on it and prove me wrong without much effort. ↩

-

It would be tempting to assume that the most efficient systems would be entirely empty except for a single passenger, but from my experience of travelling on the London Underground there is a significant speed up to be had from the flock behaviour at decision points, the inefficiency seems to be introduced at constrictions or speed changes like escalators and platform entrances. ↩

-

Ignoring the people who, after climbing the steps at a reasonable clip all the way up, for some reason stop at the top just prior to getting off. I assume that this is due to some sort of failing that means that they are unable to judge depth properly when moving, or because they can’t cope with the change of speed. Who knows, these people are probably unsalvagable. ↩