Circles

This article is superficially concerned with circles, but they are really only a vehicle for thinking about how we program a computer. It is an attempt to illustrate an important concept. The difference between local knowledge and global knowledge, or applying theory of mind to the inanimate computer – i.e. knowing what it doesn’t know.

The way computers ‘think’ and the way adult humans think are very different. We humans have incredible pattern matching and inductive reasoning powers, that pretty much anyone who is old enough to cross the road on their own takes for granted. We forget how it is to think as a child, but to a certain extent this is how we must relearn to think before we can start to program.

We have a whole suite of mental tools at our disposal, all kinds of things related to time, to distance, to space, to name just a few. However, as a child we are still to develop these tools, and so we ask a lot of questions.

During a journey A child will continually ask “Are we nearly there yet?”, no matter how many times they are told, “just another hour”, or “about another fifty kilometres” they will ask the same question in a minute or two, or whenever they reach their boredom threshold because their mental toolkit doesn’t contain the skills required to full comprehend what time and distance mean.

Programming a computer is very similar. An average cad package appears to understand circles, because somewhere between the input and the screen is a toolkit that has been developed to deal with the situations that it encounters in normal drawing. However, instead of a natural learning process, the computer ‘knows about circles’ because someone has taken the time to tell it.

From our point of view as a global observer, that is someone who is outside the screen looking onto the cad world, or sitting in the front seat of a car and turning around to yell “another ten minutes!”, the concepts of circle and distance etc. seem simple, innate even. The process of developing this understanding is what this article seeks to uncover (well, circles anyway!).

To begin to understand what is really going on, we really need to change our viewpoint and become local observers. This is a tricky thing to do as we already understand the global perspective, but if you imagine how difficult it’d be to have a concept of time and distance if you were being driven around blindfolded, now the “are we nearly there yet?” question becomes more pertinent.

The same goes for circles, computers don’t care about circles, or any of that other inconvenient stuff that we bother them with, all they care about is numbers and logic. We impose a series of logical processes on the computer that make it do some graphics that we interpret as a circle, and that series of steps is the interesting part of this article.

There are all sorts of definitions for circles ranging from ‘it is something round’ to ‘a closed plane curve consisting of all points at a given distance from a point within it’.

The big caveat to all of these definitions is that they are global observations. They rely on the observer being able to ‘see’ the whole shape in order to describe it. To be able to tell the computer to do something then we need to be able to describe things from a local perspective.

Once we get down to the nuts and bolts level, we can’t just say

‘draw a circle’ until we have told the computer what a circle is, and because computers work in finite steps, the process of drawing the circle needs to be broken down into finite steps too.

We are limited in everything we do by a certain level of granularity. If we draw a circle with a sharp pencil on smooth paper with a good quality compass, and then examine the line with microscope, we will see that it is ragged and by no means perfect.

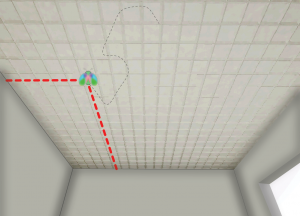

The same goes for a circle we draw with a computer. The screen is capable only of producing a fine mosaic of coloured squares, so close up, the circle that we perceive is actually far from perfect. (The same goes for a circle we print out, it’s just a much smaller set of dots)

This granularity is what allows us to actually get anything done, because if we were to strive for the implied infinite perfection in the circle we would be calculating and drawing until the end of time. We need to use a repetitive process or ‘loop’ that does something that contributes to drawing a circle each time it iterates. I’m going to discuss two methods of drawing circles, the ‘maths’ method, and the ‘body’ method.

Maths

Legend has it that one afternoon René Descartes was lying in bed watching a fly walking about on the ceiling of his bedroom, this led to him thinking about the fact that the position of the fly could be described at any instant by giving a distance from two of the walls (presumably the one by his feet, and one of the side walls, it doesn’t matter which at the moment). This was a significant moment for two reasons, firstly it debunks the theory that greatness is a reward for hard diligent work and proves that being lazy really is a good thing, and secondly because this was the birth of the Cartesian grid concept.

Contrary to what quite a lot of modernist architects would like you to believe, the Cartesian grid isn’t a real ‘thing’, it’s just a way of thinking about the position of things in space. Having said that, it’s a very useful way of doing that!

Using the convention of the X scale being left and right, and Y being up and down, if we do a little calculation lots of times we will end up with a series of points that will give us a multi-sided shape that to all intents and purposes is a circle (remember the jagged edges of the pencil circle)

X = radius·cos(Angle)

Y = radius·sin(Angle)

So radius, unsurprisingly is the radius of the circle we want to draw.

Angle in this case is the number of times we’ve repeated the process (actually it’s the number of degrees we’ve gone around, but as we are doing it 360 times, they are the same number)

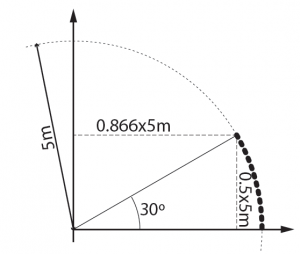

So if we imagine René lying in the middle of a field, with a pile of 360 stones next to him, and he wants to make a circle with a five meter radius. The first stone is stone 0, so he calculates that the cosine of 0 is 1, so he walks one times five meters along the x axis, then turns to face the y axis

The sine of 0 is 0 so he drops the rock and heads back to the middle and has a bit of a snooze, all this rock carrying is hard work!

After the snooze, he picks up stone 1, and does the same thing, so he walks almost five meters, turns and shuffles forwards a bit, drops the rock & returns to the rock pile.

With rock 30, he walks 4.33m along the X axis, turns, and walks 2.5m along the Y axis.

With rock 30, he walks 4.33m along the X axis, turns, and walks 2.5m along the Y axis.

This caries on until there are no more rocks.

If René had a step ladder he’d be able to see a lovely circle surrounding him. But while he was making the circle he didn’t have any idea what was going on because of his position as a local agent in the system. The circle is only visible to the global observer.

Body (agent)

It can be quite tricky to visualize the outcome of a series of sine and cosine calculations, but everyone has experience of moving their bodies about. This method of drawing a circle can be attributed to Seymour Papert, who invented the programming language Logo to teach children about computers, but this approach is just as valid when doing really hardcore stuff too!

So if we go back to our field, quite a few years have passed so now it’s a park not a meadow, Seymour is standing in the park, and he has a little trolley with his 360 rocks in it.

The first thing he does is to drop one between his feet,

Then he turns to his left one degree, and takes a step forward, and drops the next stone directly between his feet.

It doesn’t matter if he loses count of how many rocks he’s dropped as the rule is even more local than Rene’s rule, all he has to do is keep turning and walking and he’ll end up at the start.

This kind of logic is good because it allows you to take advantage of fast computers ability to do simple things lots of times.

a) Step

b) Turn

c) Repeat a

Two camps

Both of these examples are fairly trivial, but they illustrate the two main ‘camps’ of computational thinking. The scientific, mathematical approach of those who know the answer, and just want to get there as fast as possible, and the more exploratory/procedural approach of simulating systems in an attempt to find the answer.

They also show the difference between a “global” understanding of a situation. Rene is moving back and forth from the origin to place the stones, and therefore needed more prior knowledge of his surroundings. Seymour was only working locally. His only reference was the last stone he had dropped. If you work out how far each one travelled to “draw” their circle, Seymour had the easy job. This will make a mess of Rene’s reputation for laziness.

I wrote this a very long time ago for Jalal’s magazine Maeda. It never got used, so I thought that I’d post it here. It’s amazing what you can find digging through old files!