Concent - the Café with Constraints

Imagine: You’re sharpening a knife, it requires you to maintain focus. The closer you get to finished, the more likely it is to catch on the stone and ruin it all. This means that as you get closer and closer to the end, smaller and smaller breaks in your concentration can be catastrophic.

This is how I feel about working on hard things. It’s not just ‘working hard’ anyone can do that, I mean working on thing that are difficult. Focusing on hard things is hard in itself. It might be my ADHD that keeps me from concentrating like a ‘normal person’ but that constraint also gives me a motivation to find strategies to help.

I’ve been meaning to write this post for a while now, so there’s a lot to cover. Most of it is about imposing arbitrary constraints that make it easier to concentrate, by making it hard to get distracted.

The Pomodoro Cabin

Someone1 told me about a practice at a French school of architecture a long time ago2. Architecture was taught–largely–by copying drawings in those days. The school had study periods where they’d lock the student in a room, a study carrel, until they were finished. I’ve no idea what the constraint really was, but the story goes that if you didn’t finish you didn’t get out.

This painting by the Workshop of Pieter Coecke van Aelst depicts St. Jerome in his study.

As gruesomely fascinating the idea of students’ emaciated corpses slumped over partially completed drawings is, I’m not advocating a return to that. There is something in that idea though.

Enter the modern Pomodoro method. This is the idea that you encourage yourself to do something for 25 minutes, with the promise of a 5 minute break afterwards. I do this sometimes. I like it. The downside is that if your attention is weak (as mine is) there’s nothing keeping you from drifting off. There are some ways of constraining yourself with technology. These tend to be things like a Chrome extension that blocks certain websites. The problem with that is that if you are a smart and determined procrastinator, these locks barely slow you down. No Facebook in Chrome, fire up Firefox! Thus endeth the concentration.

What we need is a more severe instrument of concentration modification. Enter the Pomodoro Cabin (or cell if you prefer). This is a room, like a potting shed, that has everything you need inside to work. Somewhere to put your things, somewhere to sit or stand, water etc. There are a few little tweaks that stop this being just like a Google phone booth3:

Odysseus and the Sirens, eponymous vase of the Siren Painter, c. 480–470 BC, (British Museum). I love me some Black Figure Vase painting. It’s like Ινσταγραμ for the Greeks!

- There’s a lock on the door: It has a timer lock that is only controllable from the outside. By going in, you are committing yourself to a period of time. You don’t have to work, but you might as well because you can’t do anything else. This has some strange side effects. If you forget something vital you’ll just twiddle your thumbs until you can get out; teaching you to be more organised. It also stops you from rage quitting and going for a walk as soon as you get stuck, maybe upping your persistence.

- There’s a Faraday cage around it: You can’t make calls, or get Instagram notifications in the cabin. You are committing to your concentration being controlled by an internal locus.

- It has it’s own WiFi: to extend the previous point. The box can’t get WiFi from outside, so it needs to provide its own. The key point here is that you can disconnect it before you go in. This cuts you off from any access to the outside world, further reducing opportunity for distraction. There is a lot of work that needs the internet, but if you can chop it into chunks that do and chinks that don’t then you are more likely to stay focused in the don’t chunks.

When I started thinking about this I was using an air freight container to hold the box. I’m not sure why really. I think I also drew this with the person facing the wrong way!

The idea for this might well rest on the stories people tell about being productive on long distance trains! (At least ‘back in the day’ before trains had WiFi.)

The Concent Café

Mediævel Scriptorum, taken from Where Are the Scriptoria? on medievalfragments

This idea is pretty strongly based on Neal Stephenson’s book Anathem4, but also on some other bits and bobs that I’ve been thinking about monastic life. The Hours that “mark the divisions of the day in terms of periods of fixed prayer at regular intervals”5 is pretty comparable to the idea of work. In Religion for Atheists Alain de Botton bemoans that we’ve ditched all the useful stuff that religion did, much of which pre-dated organised religion, or emerged as organisational strategies learnt while running the largest and most powerful organisations in the world.

I’m not advocating that we all go and work in Concents on Mathic philosophy6, I’m suggesting that we pick over the bones of religion and see if there’s anything that’s still useful.

Here’s a bit of an explanation of the background, mostly it’s not required to understand what I’m about to say, but it’ll be useful thinking material to ground you. In Anathem, the avout–intellectuals separated from Sæcular society–live in concents which are monastic orders. The thing that’s a bit hard to get your head around at the start is that they aren’t theist or deist, they have merely separated to protect human knowledge from societal collapse and fashionable influence. They have a thing called apert here’s an explanation of The “Discipline” from Wikipedia:

the avout are separated, both mentally and literally, from the Sæculum, or outside world. There are different levels of separation. For example, within a concent, there are different terms of residency. There are 1-, 10-, 100-, and 1,000-year orders. Each of these celebrates “Apert”, a festival opening the concent to the outside world and allowing the flow of information between them, on an interval determined by that number. For example, a 10-year order would celebrate Apert once every ten years, remaining isolated otherwise. Likewise, a 100-year order would only celebrate Apert every hundred years, and a 1,000-year order once every 1,000 years. It is an essential part of this that at any time an order celebrates Apert, all orders below it also celebrate Apert. For example, a Millenarian (1,000-year) order would celebrate in the year 3000. Because 3000 is also a multiple of 100, 10, and 1, Centenarian, Decenarian, and Unarian orders would also celebrate.

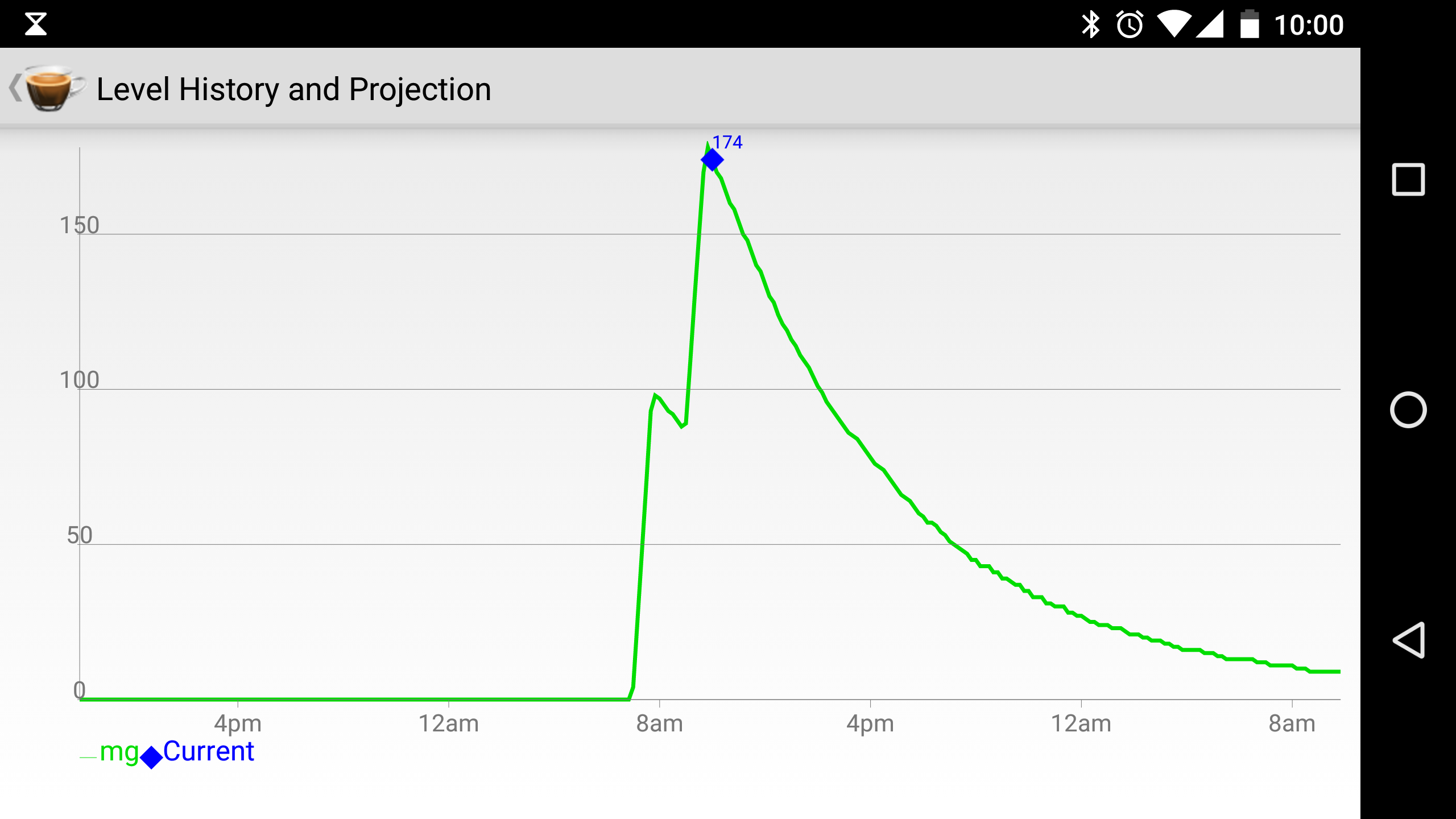

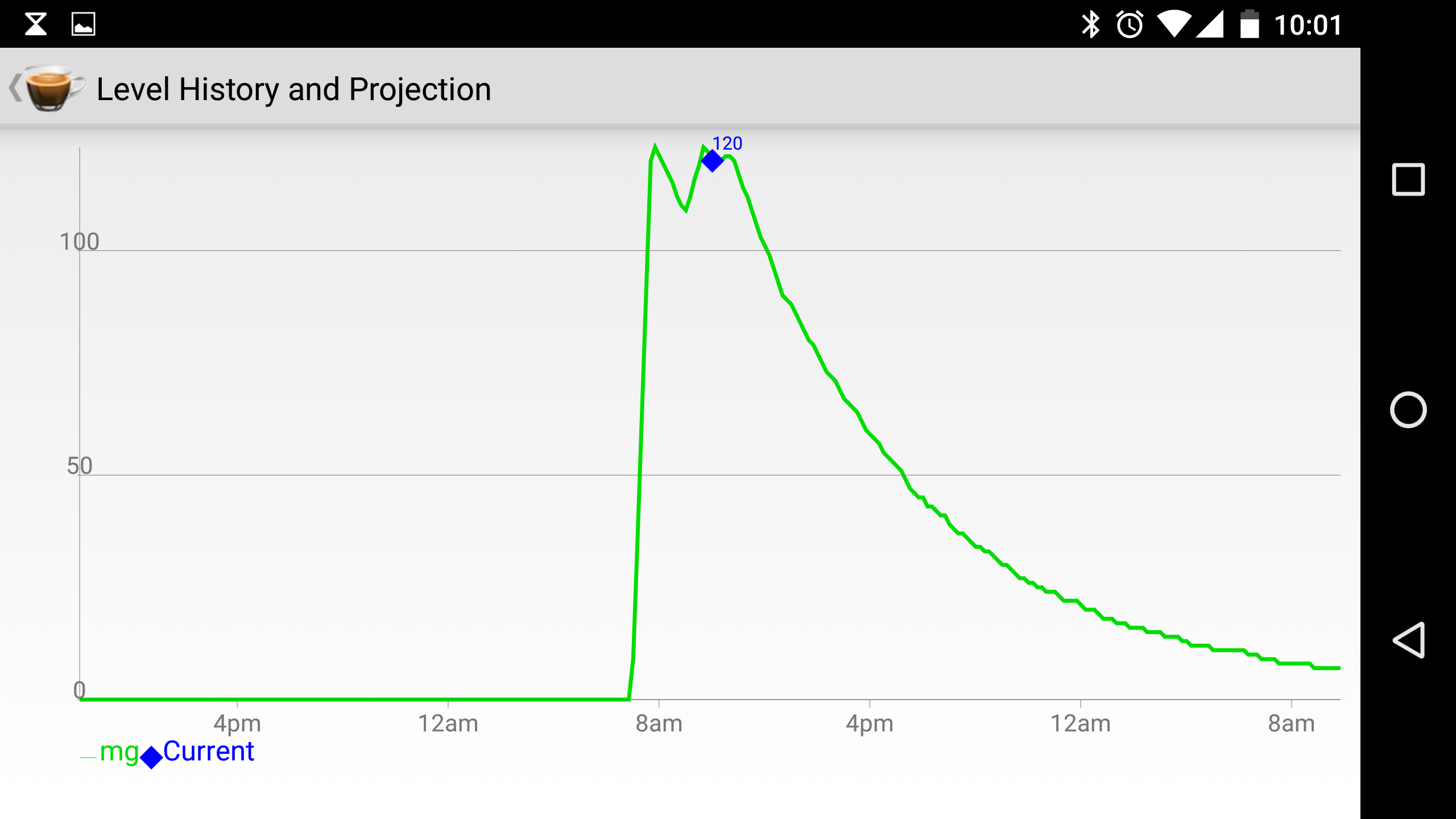

These are screenshots from a caffeine tracking app I’ve been using a bit. It’s crusty but it’s instructive. Assuming that a constant level of caffeine is a good thing, then it’s best to keep it constant with small bumps. Making one ounce filter coffees is impractical, but making eight of them is a piece of cake. The novices could just provide another cup every time their tracking software tells them to. (Based on body weight or even some other fancier caffeine metabolism calculation.)

OK, back to the Café. You can see how the idea above is a bit like the Pomodoro Cabin, just on a bigger scale. You and your philosophy buddies are locked in a castle for 1, 10, 100 or 1000 years. Knowing that you won’t be distracted for another 900 years will really clear the mind.

The idea of the café is that you are doing your pomodoros, but in a group. There is peer pressure to maintain concentration7. Some problems aren’t solvable in 25 minute chunks. So the café would have different rooms with different lengths of pomodoro.

This gets tricky when you need to maintain for long periods. You’ll get thirsty, your caffeine levels will drop. In general you need support8. Enter the novices. These people are doing a job, it might be full time, or it might be a rota of people who would otherwise be working but want a longer break and a change. They would provide support, topping up people’s water and cups on a schedule.

Lindisfarne monks working up to becoming the Xerox corporation. From The Vikings. Isn’t TV great!

As I was saying earlier about picking over the bones, I don’t think that you’d use these things all the time. Maybe you’d use them more once you started to build up your attention muscles, but these would be used in conjunction with other work settings. Figuring out what setting is best for what type of work is a skill that–as a society–we aren’t good at. We value conformance and consistency too highly (as did the monks). We need to get out of that mind set and into thinking of picking the right tool for the job, where your setting/context is one of those tools.

-

Matt Gaskin I think ↩

-

The École des Beaux-Arts I think ↩

-

Word is that they don’t have phones on their desks at Google. I’m all for this. They go to something like this to make calls.

↩

↩ -

I really enjoyed Anathem. It’s extremely long, so be warned. It’s got a theme of permanence that runs through it, so I bought a hard copy! (It’s inspired by the Long Now Foundation.) ↩

-

as they do in Anathem. ↩

-

Some people already do this via the magic of the internet. E.g. the Less wrong study hall ↩

-

This is a nice story about pissing while still at the bar in Baltimore pubs. I’ve heard similar stories about Australian pubs and it’s probably universal. Maybe this problem could be solved in a slightly more space age way these days! ↩