Time factors

I’ve been thinking about time recently. Not in a spacetime sort of way, but in a much more prosaic way; the time we spend at work. (And its inverse, the time we don’t!)

Reading stats (no footnotes)

ReadabilityGrade 7

Paragraphs66

Sentences161

Words2308

Characters12750

Letters10163

Read. Time00:09:13

I was on the plane to Brisbane and all the ideas that were swimming about in my brain came into focus for a moment. I frantically scribbled it all down in my notebook and I ended up with these 7 graphs. The thing I like about them is that they just describe the way things are; you can read them however you like. I’ll give you my interpretation of what it leads to.

I’m going to make some assertions based on personal experience here. Some of them may even have evidence to back them up. If evidence exists I’ll footnote it as a reference. I’ll expand on my own experience as footnotes too.

These 7 points aren’t to be read as a story, but as if they are just ideas to hold. Then we can have conversations in the future and use them as points of shared understanding.

If you want to jump straight to an idea then here are some handy links:

- Productivity per hour

- Capital cost of more people

- Communication overhead

- Our workload

- Kaikaku

- Slack

- Donated time

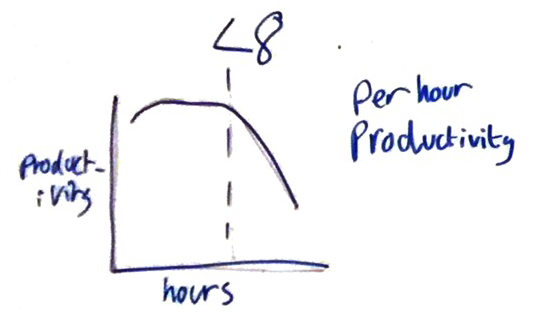

Productivity per hour

There are a few big types of work. Most studies focus on people who make widgets because their productivity is easy to quantify. Either you make 500 widgets or you don’t. Some office work is like this; maybe you process 100 application forms. It’s much harder to study knowledge work because productivity could be measured in any number of ways, all likely to be inaccurate1. “Because it’s hard” is a terrible reason not to do something, but it does explain why there seem to be so few studies on productivity per hour in knowledge work.

If we talk about manufacturing, there’s a long history.

On January 5, 1914, the Ford Motor Company took the radical step of doubling pay to $5 a day and cut shifts from nine hours to eight, moves that were not popular with rival companies, although seeing the increase in Ford’s productivity, and a significant increase in profit margin (from $30 million to $60 million in two years), most soon followed suit.2 3 4 5

Ford wasn’t motivated by social factors6, he had a clear profit motive. There was compelling evidence that per-hour-productivity started to drop off after 8 hours.

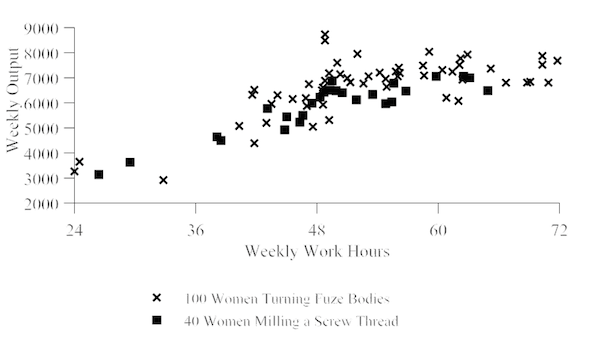

This finding was backed up by some studies done in the first world war. Here’s an Economist article that explains it, and here’s the paper that they base the article on.

What we can see there is that the women7 who worked a 48 hour week got just as much done as those who worked a 72 hour week8.

This was still the case between 2000-20059. Work becomes ever more complicated so I can’t see this trend ever reversing.

As a wild and unsupported prediction: If your job requires you to think hard, then you probably can’t even maintain high level output for 8 hours!

Here’s a quote from that Economist article:

these results say nothing about output in service-sector professions, where most people in advanced economies are employed today. I would bet, though, that the results are even more pronounced. For work that is largely self-directed, and which requires intellectual engagement, you may achieve more in an hour of hard work than in a day’s worth of procrastination

There have been lots of articles recently about moving to 6 hour days. Academic, pure mathematicians often do 3 hour days. If our10 work really is knowledge work11 then I’d imagine that something similar applies to us too.

This is a simplification. People’s productivity varies over the day, varies by their mood, their diet, the weather etc. You can’t just say that people need to work a certain amount. Paul Graham’s essay ”Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule” talks about working in intense blocks. Sometimes it takes time to get into a problem.

To work with other people in a sustainable way, we need to keep some kind of Sustainable Pace.

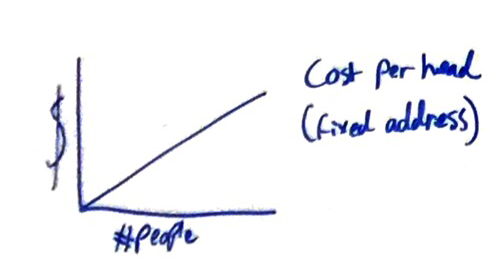

Capital cost of more people

As you add more people you need more space. That means more desks, more rent etc. The cost goes up more or less linearly12.(Assuming one person per desk.)

As you add more people you need more space. That means more desks, more rent etc. The cost goes up more or less linearly12.(Assuming one person per desk.)

That means that there is an incentive to get people to stay at their desks for more time to extract maximum value from that investment. It doesn’t matter as much that they aren’t producing as much because that loss is offset against the loss from having the chair empty.

This is a pretty easy one to solve; Activity Based Working (ABW) and other free address theories mean that you can drop the people:desks ratio. In our office there is never a 1:1 people to desks ratio. I’ve done a few rough studies in the past and it’s more like 60% as a general maximum13. That means that we are “wasting” capital; it’s not being fully exploited14.

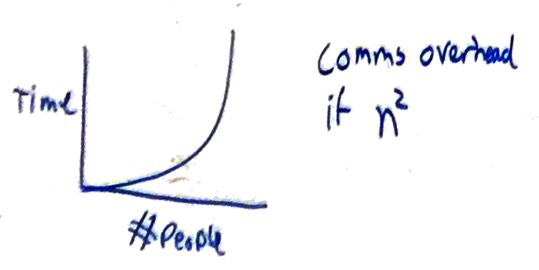

Communication overhead

In The Mythical Man Month Brooks talks about how adding more people to a project that’s running over time will just make it run even later. The gist of that argument is that more people means more communication overhead. it could get as bad an an n2/2 problem (where everyone needs to talk to everyone else).

In The Mythical Man Month Brooks talks about how adding more people to a project that’s running over time will just make it run even later. The gist of that argument is that more people means more communication overhead. it could get as bad an an n2/2 problem (where everyone needs to talk to everyone else).

Cyril Parkinson wrote a series of semi-satirical articles for the Economist about how the world works. One of his laws is about how large an organisation needs to be before it becomes entirely self sustaining from internal busy work15. To unpack that idea a little, it means that everyone in that org is completely occupied by going to meetings about meetings, reading minutes, strategising their career etc. and nobody is actually producing any value for a customer.

This is an old way of thinking about things with strict hierarchies and almost no Information Technology16. These days we have Trello, Jira, Basecamp etc. to help us. We can communicate asynchronously and get the right information to the right people. What that means is that the communications overhead doesn’t go up exponentially with each extra person. If you get your communication culture right it might even go down as more people in the network start acting as information aggregators.

Our workload

One thing that most people will say when they hear this kind of stuff is well that’s great, but I can never get there, I’m too busy!

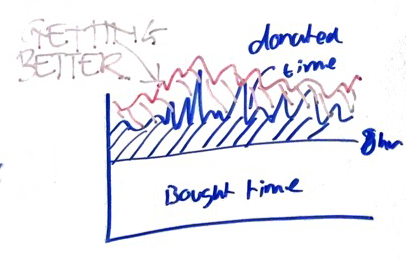

That’s a totally valid thing to say. Craig Burns drew up a terrific set of diagrams that explains how our workload has changed over time17.

Kaikaku

This is a concept taken from the lineage of Toyota’s lean production doctrine. Kaikaku is Japanese for radical change. It’s the idea that there must be some kind of chaos before a new era.

If the ideas in Craig’s slides above are true then we will need either a miracle or huge chaos before we can escape that pressure.

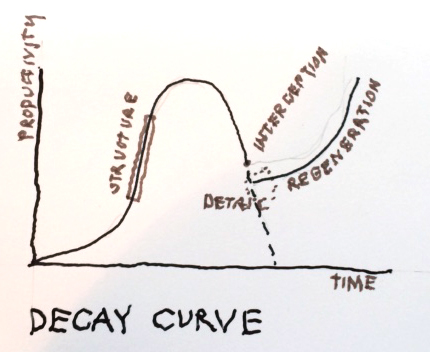

Graham Bligh uses the same concept, but by a different name, he calls it the decay curve.

I think that adding a third version of this in might be helpful too. This is the asset deterioration graph of a road.

This graph shows that as you use a thing it deteriorates. Then you repair it, but it doesn’t go back to its new condition. Eventually it can’t be easily repaired to a level that is acceptable. Then you need to do a full refurbishment. This happens with expensive shoes. You polish them every week, but after a few years they look tatty, so you take them back to the shoemaker. They will dismantle them and put them back together for you.

This feels to me like what most organisations do at the moment. People are busy, over time they get tired, so to keep their spirits up there are little injections of enthusiasm. In order to make an organisation become something new it needs a really major injection of chaos.

Things like Christmas parties and the Futures Forum are good injections of energy, but for there to be genuine structural change there will need to be a more sustained and forceful level of change. It will be extremely painful, a lot of people will oppose it. It will be risky too! There might even be a substantial chance that the organisation won’t survive it; if they do they will be better off!

Slack

This isn’t slack, like the communication platform, but the idea that we need space in our lives to reflect and regroup.

This isn’t slack, like the communication platform, but the idea that we need space in our lives to reflect and regroup.

Google famously had 20% time. Zara runs their operations at something like 80% of maximum capacity18.

The general idea is that if you are running flat out, then it’s really hard to change direction. Architecture, as a profession, is running so flat out that it doesn’t even have time to tie its shoe laces! People are bored of The Axe Quote, but I’ll put it in anyway19:

Time spent in sharpening the axe may well be spared from swinging it.

The spare time that Google, 3M and Zara create allows them to invest in improvements. In Google’s case, they were mainly investing in making new products. They were in a divergent phase where they were experimenting to see if there were new areas that they could grow into. Zara uses the slack to be able to respond immediately to market forces.

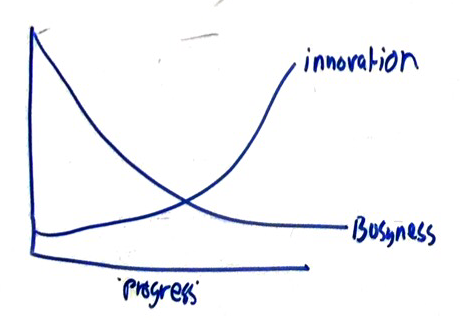

In architecture there is so much accumulated technical debt that the first thing that would be addressed would be paying down that debt. That’s the left, steep section of the graph. In that period benefit would accrue really quickly as knowledge sharing produced benefits with very few disadvantages. In this phase we’d be trying to capture more of the value that we already generate.

Once most of the technical debt is paid back we’d go into a divergent phase where we–like Google did–search for new business models, develop new products and services. Trying to generate more value whilst figuring out how to capture that new value.

Then–again as Google did–we’d go into a convergent phase where we focus on the areas that are really working. My guess is that there is a long time before architecture gets to this phase!20

Donated time

This is a nuanced topic, and it really gets people on edge.

This is a nuanced topic, and it really gets people on edge.

If one’s salary ‘pays for’ 8 hours of work, then any additional work done is donated. This is a definitional minefield. What is work? Are we time based or task based?

Currently, the way most contracts are written, we are time based, so I’m going to go from that basis.

Sometimes it’s easy; paid overtime means that there is no trade off to work out, time=money21.

Given that hardly anyone in architecture pays overtime, there must be some other motivation to sacrifice time that one could be using in other ways. Why would you work for free when you could be spending time with your kids or your friends? You could be doing some other work that earns money, or doing something for yourself that you currently need to pay someone to do.

In other words what do we gain by working these donated hours?

I’ve asked quite a few people, I got a lot of answers.

One that comes up a lot is that people try to work for 8 hours day. They offset trips to the toilet and coffee breaks–times that they are doing non-productive things–against the platonic 8 hours. This is admirable I guess, but it feels a bit wrong. That would make sense if we were production drones. If we stamped widgets, or were doing process work, but we claim that we are doing thought-work22. If we are thinking then most of the progress in thinking happens during coffee breaks and on the toilet. If making up for lost time is the reason then we’d expect to see the levels of work being more consistent. E.g. people would work 8.5 hours because they spend 30 minutes drinking coffee and pooping.

The next most common is that there is a sense of career advancement that comes from ‘putting in the hard yards’23. You just need to do the hours to show your love for the work. People feel that they have a responsibility to the project and that translates into doing extra work on their own time24.  The last argument relates to the previous one, but the time is given less willingly. If there is

The last argument relates to the previous one, but the time is given less willingly. If there is

- a certain amount of work that needs to be done,

- there are a certain number of people allocated to do it,

- and there is a time that it needs to be done by.

We aren’t willing to compromise on quality so we try to cram that work into a smaller time. There are 16 extra hours every day that we could do the work in! This feels like a huge failure of resourcing. Although I’m not entirely putting the blame on the people who allocate the people to jobs. Much of the blame goes to poorly filled in time sheets, and to the cultures that encourage that to happen.

Craig also has a great diagram that explains this problem (and how to fix it).

The problem is that the how is only specified as do things better. Finding an actionable how is going to be hard.

Conclusion

I’ve presented 7 ideas. They don’t explain everything about time but I’ve found them very useful as a common touch-point with people.

I’ve tried (not very hard) to keep my opinions to the footnotes. I have some conclusions that I’ve drawn from these premises. What I’d really like is to see if others come to different conclusions!

I’ll share mine in another post.

-

This is talked about a lot in The Mythical Man Month, about how many lines of code a person writes in a day. Then software people have been trying to not do that ever since. ↩

-

New York Times “Ford Gives $10,000,000 To 26,000 Employees”, The New York Times, January 5, 1914, accessed April 23, 2011. ↩

-

Ford Motor Company “Henry Ford’s $5-a-Day Revolution”, Ford, January 5, 1914, accessed April 23, 2011. ↩

-

Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. “Ford: Doubling the profit from 1914-1916”, Hispanic Pundit, 1996, accessed April 24, 2011. ↩

-

HispanicPundit “Economic Myths: The 5 Day Work Week And The 8 Hour Day”, Hispanic Pundit, September 21st, 2005, accessed April 23, 2011. ↩

-

others in this period were to some extent. E.g. My mother went to the school that Cadbury made for his workers in Bournville. ↩

-

It was women, the men were all off getting machine gunned down in muddy fields. ↩

-

to fit in a 72 hour week you’d need to do between 10 and 14 hours a day! ↩

-

according to Holman, C.; Joyeux, B.; Kask, C. 2008. “Labor productivity trends since 2000, by sector and industry”, in Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 131, No. 2, pp. 64-82. ↩

-

when I say “our” or “us” I mean BVN, but it applies to all knowledge workers. I wrote this for the BVN internal blog, so they are the intended audience. ↩

-

I think that the uncomfortable outcome of this line of thought is that a lot of the work we do isn’t thinking. It’s on a gradient between pure thought and pure doing. With 96% of it quite close to the doing end of things. My post on automating architects talks a bit about this; the doing tasks will be automated. ↩

-

It’s not strictly linear. There would be discontinuities when you need to move office because it’s full. Things like bulk licencing deals are similar; 200-250 Revit licences cost the same, but your 251st licence costs a lot more. ↩

-

the first was done using Greentrac to measure the number of active computers. This isn’t perfect because not everyone at a desk is using their computer. They may be leaning back in their chair on the phone, or drawing. Even if we bump up the occupancy rate by a generous 5% that’s still much lower than 100%. The actual number went from a peak of 60% down to 40% during lunch time. ↩

-

I don’t think anyone feels bad about exploiting chairs and software licences, but I’m using exploited in the economics sense, not the bleeding hearts sense. ↩

-

I don’t have the exact quote, Matthew has my copy of the book at the moment. ↩

-

It’s really easy to forget that IT is about information and communication. We get so hung up on the technology thing. “Fix my computer” etc. that we forget that Uber is IT, that Facebook is IT, that fruit in the supermarket is IT. ↩

-

I’ve put this in a footnote because I’m trying to keep my opinions out of this piece as much as I can. I have strong feelings that this is because architects have let themselves get squeezed from both sides.¶ Architects agree to more work than they are able to do as part of a sustainable business model. The other side is that clients see other industries being able to handle much larger workloads. Those industries have realised efficiency improvements from IT and have automated much of the drudge work.¶ If architects don’t a) put forward a compelling value statement, and b) work hard to automate the menial work that makes up >80% of their days then I can’t see that trend reversing! ↩

-

hilariously the main study on this seems to be by a guy called Nigel Slack. This essay references it, but I haven’t fully chased it down yet. ↩

-

This seems to be another misattributed quote! I’m getting really interested in these. This one seem to not be From Abe Lincoln at all. If you like these sorts of things, it turns out that nobody can find a source for Keynes’ “When the Facts Change, I Change My Mind. What Do You Do, Sir?” ↩

-

If it ever does. There’s is a good chance that the current value generated by the profession will soon come from some other party. People say “We’ll always need buildings”. I agree, but there is no first-order truth that says that architects need to be the ones providing them. It’s our job to make sure that we provide better value than anyone else is able to. ↩

-

notwithstanding the presumed loss of productivity per hour that I talk about in the first section ↩

-

maybe we’re not, but nobody ever admits to it. Some of history’s most famous people didn’t work crazy hours. E.g. Descartes’s laziness was legendary!: ↩

-

which is odd in a fully metric society, surely you’d be putting in the hard meters? ↩

-

in the spirit of keeping my opinions to the footnotes: I think that this is really dangerous. It sets a precedent that if you are unable to put in extra time because of commitments to family or something like that, then you aren’t as valuable. This seems completely at odds with the cultural change that organisations like Parlour are trying to bring about. More selfishly, if the reason you are working longer hours isn’t because you did something wrong and are fixing it, then it’s probably a project resourcing error. As I’ve said above, the MMM idea that more people means less work done doesn’t apply any more. ↩