Autonomous Wardrobe

Note: I wrote this in February, but I didn’t finish it. I’ve decided that as nobody reads my blog, that I’m going to post and update, rather than perfect and post.

In time, things will get more finished, and this note will disappear. Feel free to comment in the meantime though!

I want to explain my self driving wardrobe idea, and how the future unit of space is the Uber eats bag. It can probably be several posts, with the general argument being:

People keep stuff in their cars. For convenience, but also for preparedness. This stuff falls into a couple of categories:

- Tissues are there for convenience and so could potentially be replicable by a service. I am happy to use the tissues, or water, or mints in an Uber because they aren’t personal.

- People keep golf clubs in their car for preparedness, with the mindset then I can golf at the last second.

This idea was prompted by watching parents unload all their baby-hardware from a car. All that stuff is apparently needed the baby-thing alive and functioning properly, and a lot of it lives in the car.

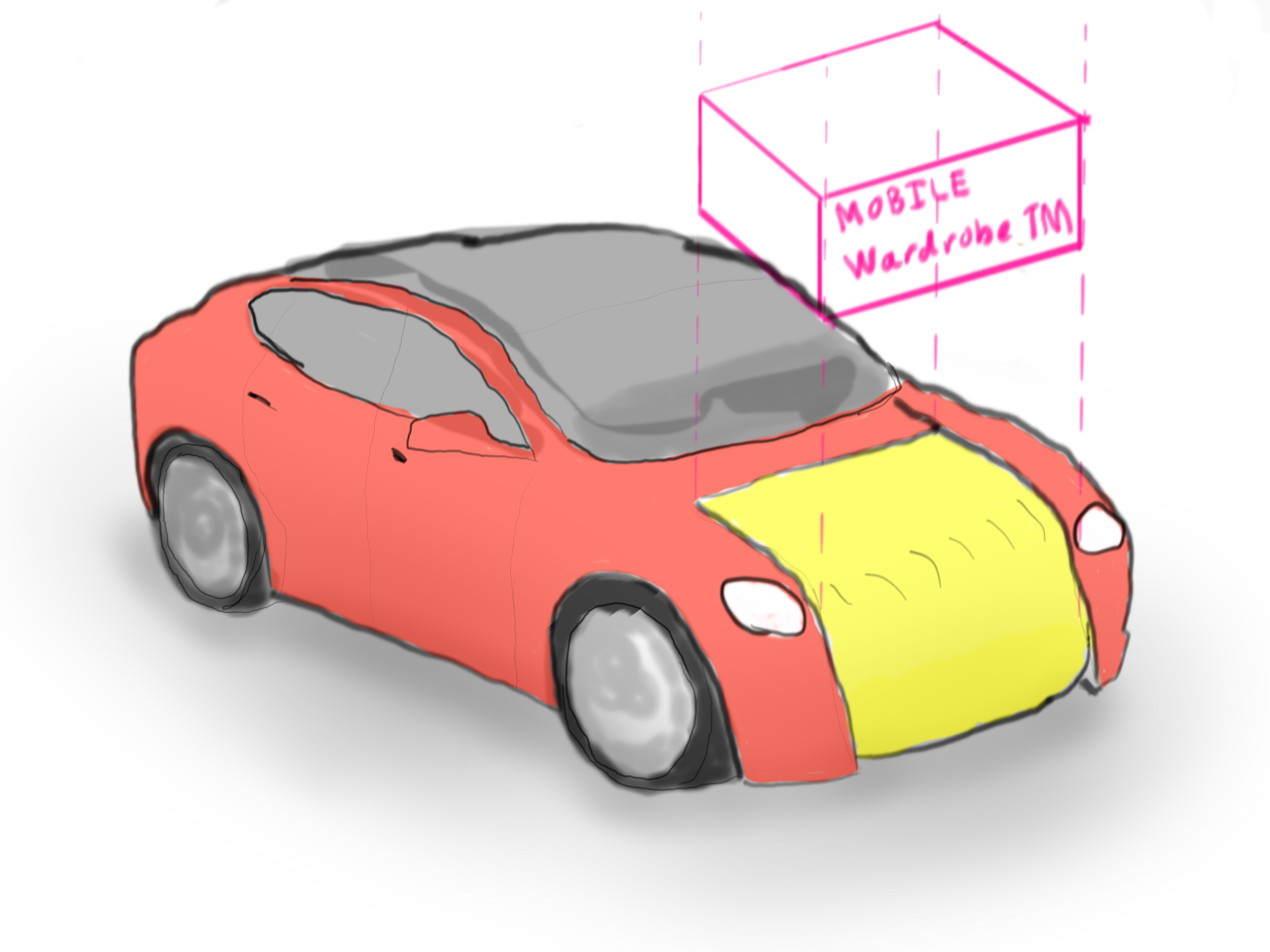

[diagram here]

If I had a car I’d leave all my adventure stuff in there so that I could spontaneously do a thing. This convenience is a luxury that we’ve become accustomed to. We think of horses as a singular thing now that they are mainly pets for rich people. But when they were the backbone of the communication and transit network, changing horses was commonplace. The postal service would have a fleet of horses that you’d use on demand—much like a Waymo—and then drop off when you’d finished that leg o the journey. [Check this and get some refs up in this place] You’d climb from the saddle and take your hardware and saddle bags into the saloon or tavern for the night. The next day you’d pick up another, different, horse and off you’d go. This requirement to “take all your personal belongings with you” is the same in modern life with Uber or a plane. Having a mobile wardrobe is actually a recent, and in the grand arc of history relatively short blip. However, it’s a comfort that we’ve come to rely on which brings us to a fork in the solution design space: do we design out the need for a mobile wardrobe by moving an almost infinite amount of utility to the boundary, or do we work with the wardrobe?

My intuition is that most people (including me) will try to solve for utility at the point of use, after all, minimalism is for rich people. So, because it’s fun to be contrarian, what happens if we pull on the thread of keeping the status quo? (whatever that means, reality seems to be liquid, taking on the shape of our preconceptions) and mental models. ∴ if we change our mind, reality changes too.)

Lets restate the problem and see if that gets us anywhere:

- People find it convenient in their cars. Either because of a regular need for that thing (tissues, sunglasses, sun cream, coins for tolls, CDs, etc.[^cds]) Or for an infrequent, but high value need (golf clubs, snowboard, etc.) [These things always go via the car on the way to being used, maybe recycle the diagram, or a reference to it.]

- This is something that, in this version of reality, we are trying to maintain.

- Private ownership of vehicles by individuals is going to be replaced by easy access to a fleet of on-demand vehicles (it doesn’t really matter for the moment if they are autonomous)

- A point of friction/[dis something] comes up because in the shift from private to fleet the ‘feature’ of the mobile wardrobe is lost.

[diagram argument map]

A little diversion, I read a lot of speculative fiction that’s interested in building worlds (rather that literary fiction that explores the world we’re in.) World building is interesting in itself, but mostly it’s useful because it explores the adjacent possible. Temporarily exploring another world gives the reader some perspective on our own world. Much as travel broadens the mind, imaginary travel does too. A couple of years ago I realised that most of the authors that I was reading were like me—guys, anglo, well off (Neal Stevenson has almost the same haircut as me!) SO I tried to read authors who looked less like me. I didn’t do very well, I just ended up mainly reading a lot of Margret Atwood and Ursula le Guin, but it did start to shift my mindset to add “What would this experience be like for someone not like me?”. That’s how I came across this question because the default me would never have found it. I’m a long term non-user of mobile wardrobes. Trains, motorbikes, busses, bikes, if you want it with you, carry it on your back.

Most current autonomous car designs seem to be extensions of public transport (early Google) or an airport lounge on wheels (car companies)1. Both of these modes disregard the material aspects of personal space; what can we do to solve for that? One possible model is chests and porters.

[stagecoach image]

As an aristocratic person, getting out of my coach, I’d just walk straight into my hotel without looking back, safe in the knowledge that a porter was taking care of my luggage. In the simplest terms, my things were in a box, they got themselves onto a vehicle, got to where I was going, then followed me to my ultimate destination.

[box with wheels image]

In the chests and porters model, the box comes with me. It could be in, or on, or alongside the space that I’m in. If you continue to factor things out, then it doesn’t really matter if the box is actually with me on the journey or not. Really all that matters is that the box is there by the time I actually need it. Let’s call this the airline luggage model. Imagine that you’re flying to London from Sydney, via Singapore, with a longish stopover—total time of T. As long as your bag gets to London in a time that’s <= T then you’re happy. That leaves the airlines free to trade baggage and arbitrage the routes a bit. I don’t know if they do that, but it’s a possibility. You might take a scenic route to work, and your mobile wardrobe might take the direct tunnel.

If you don’t care that your mobile wardrobe is going to take a different route to get to your destination than you are, then you probably also don’t care where it lives when you aren’t using it. If I live T minutes away from the beach, or the golf club, or the ski hill, then I know that my beach, golf or ski box also needs to be T away, but not necessarily in the same direction as I am.

[overlapping radius diagram]

Which might mean that I could have boxes all over the place, and as I register my intent to do an activity, my box for that activity would start to shuffled around to get to where I need it to be. There could be predictive optimisation on the boxes too. If it’s raining and cold, few people would be retrieving their beach box so it could be shuffled to a less accessible place.

There might be a concern that moving a lot of boxes around might produce a lot of traffic, but as long as there isn’t too great a rush on them they can be tagged onto existing journeys. THe urgency could be managed by changing pricing with urgency, encouraging people to give advance warning, maybe just by putting an event in their calendar.

I have thoughts about how big a box would be, but I’ll get to that in a future post.

-

Waymo’s minivans don’t count because they’re not really designed to be autonomous from inception, it’s retrofitted. ↩