Ethics of data collection for buildings and their occupants

I had a coffee with Rhys Goldstein1 today, he showed me some of his work and we had a great chat. He had the idea that a framework for collecting data about building occupants and their behaviour would be really valuable. It would make it possible to combine data from different environments and build up patterns across different situations. Currently there isn’t a standard which means that the data can’t be readily combined. Rhys has some great papers from around 20102where they simulate user behaviour, but further progress in that area is held up behind a dearth of real data. It feels like they’ve gone about as far as they can with hypothetical people, and the theory needs to be tried out on real people.

Tl; dr.

Collecting lots of data is essential to making good simulations of buildings. Most buildings exist to contain people. People are sometimes a bit odd about data being collected. This is reasonable because data is often misused or leaked. Below is an attempt at outlining the problem and what to do about it.

The ethical mandate

This is a topic I’ve thought about a lot, but know little of the formal issues surrounding it.

The way that buildings are designed today feels to me a bit like the way barber-surgeons practised medicine. There is a vague understanding of the way that the system operates, an accumulated set of heuristics of what’s worked and what hasn’t (but no general principles to back that up)3. I don’t have a grounding in medical ethics, but I can’t help feeling like there must be some fruitful concepts to borrow. I’d imagine that people will counter argue that we know a lot about how buildings respond to the sun, or to wind loads. This is true, but that’s essentially physics, and so given enough information is essentially deterministic4. It all gets messy when humans are introduced.

We need to fast forward a couple of centuries and take advantage of the technology that has been made available to us as it spills over from other industries (sensing, wireless communication etc.) and develop a deeper understanding of the environment that building design is practised in.

I’m going to talk about we a lot. When I say we I mean everyone who has a stake in getting buildings built. Probably only up to the point where the design is frozen and then executed in our current model. So that’s engineers, architects, planers, developers, various design consultants (who have I missed?). In a future model where buildings are more continuously monitored then it will be a much longer and more interesting process.

It feels irresponsible to create environments for people to live and work in without having a more rigorous way to assess our designs. Buildings have very long lifespans. It’s not uncommon for a building to be expected to last 50 years. It is unlikely that we would tolerate experimentation over such a long time span in other domains5 when a less committed method6 is available. Our problem is that a less committed method is not yet available. We have all the pieces in place to develop such a method. We know the mathematical foundations of simulation; we can make immersive environments in virtual reality; the building physics and meteorology needed to model the way that the physical environment influences the building is well understood. What we don’t have is the data to back up a simulation of human behaviour in buildings.

My assertion here is that we—as a field concerned with the human aspects of building design—are being negligent7 in not addressing the lack of data that makes it impossible to do good occupancy simulations. Following from that, we ought to do something about it, but it’s not obvious how to start. This is what I’ll try and work out below.

What I’d like to come up with

I’d like to establish a way to collect data about buildings and the ways that their occupants interact with them. It should be usefully detailed—but not intractably so—and it shouldn’t harm any of the parties involved8.

This is a multi-pronged problem.

-

How do we collect enough data to be able to say that we have a good understanding of a person?

People are complicated and need many dimensions to describe their lives fully9. How many of those dimensions do we need to collect data on to make a good enough representation of their behaviour. Is there some kind of Pareto ratio that 20% of the things we could measure give us 80% of the world that we care about?

What data do we need to collect and what format should it be in? Acknowledging that future people will want to collect more and different types of data, how would they go about extending that standard?

-

How do we protect that person from undue privacy incursions?

It seems as if individuals have quite a complex attitude to data privacy10. People are often hostile to efforts to collect more data about them, but are rarely motived to find out about what is harvested without their knowledge.

-

How do we reimburse the measured person?

The person being tracked is transferring value to another party. Is it just that they get to live in a better world?11 The example that usually comes up is the exchange of value between Google search users and Google. They are given access to enormous amounts of data, in exchange for looking at some adverts. Fitbit activity trackers do something similar by recording data and then rewarding the user with an explanation of that data. (I don’t know what Fitbit plan to do with the giant data store they’ve built up.)

In this context could enough value be created by just data products12 or would you need to provide some sort of other inducement to cooperate? (cash, free things etc.)

The first two of these are in tension, and the third brings an uncertain economic angle into the equation.

Problems

There are two broad categories of problems; ethical concerns and technical concerns. They overlap substantially.

-

Not all collection runs will collect all types of data

One of the problems that this is trying to overcome is that each research team is recording, storing and accessing their data differently. We need a way to standardise the collection methodology, the data format and the queries so that different groups can combine their results to provide a larger corpus.

There will also be people who only collect weather data13 or only collect movement data. That’s still very useful as it bolsters the reliability of the models that deal with those phenomena. This should be able to handle that. Something that we’ll need to deal with is working out if results are applicable to a particular context. Humans probably move in a pretty similar way in most contexts, but can I leave the data from submarines in when training my model? This is probably a good problem to have, it means that there’s enough data to be able to see similarities and differences.

This also needs to be able to evolve without needing to scrap the existing data (unless it can be shown that it was bad data). If we start sampling movement data more frequently or with better accuracy then the historic data still has some use. This will mean that we probably also need to store an error bound with each entry (or maybe set).

-

Providing anonymity to users (those being tracked) is at odds with collecting detailed data

To get really good insights it helps to know a lot about the world. It might end up being relevant to know someone’s age, if someone is pregnant or if they walk with a cane. Those data points can work like a giant game of guess who to work out who a person is. For example the public taxi data can be used to find a celebrity’s home address (here, here and here) by joining other public data sets. E.g. a photo that shows someone getting out of a cab. If you can see the cab’s medallion number and you know the time you can reverse the data to get the journey.

-

Collecting demographic data (e.g. ethnicity, gender, income etc.) is likely to be seen as overly intrusive, but without it there is no way to ensure diversity in the data.

These data are generally considered not pertinent to most scenarios, it shouldn’t matter to Pepsi that I am a mid 30s male14. It does matter if we are creating simulate populations of people because we need to know that we have a representative sample. There has been a recent interest in Artificial Intelligence’s White Guy Problem which, in summary, is that the training sets that machine learning algorithms are provided with are biased, and that bakes bias into the resulting classifier.

There will probably be a period when there is a lot of data that seems unnecessary. People might make the claim that it’s unethical to collect it, or that it’s never going to be needed. It’s important that we are collecting attributes, rather than categories. This distinction is subtle, but it means that you can do your categorisation later. E.g. collect heights, not just if someone is in the tall person category or not.

Without the demographic information we run the risk of training the simulations on data sets that comprise of the habits and behaviour of an overwhelmingly male, middle class group of academic nerds.

-

These data are of benefit to everyone, but how can it be sufficiently anonymised to protect the privacy and safety of the individuals?

My initial feeling is that this needs a query engine working on an encrypted database. Raw data is too easy to deanonymise (E.g. Netflix15)

The database that stores the data should probably not be directly accessible to anyone. This is a bit like the way that Apple can’t crack their own phones and LastPass uses client side encryption so that nobody can access the data (it’s encrypted before they get it so it’s just garbage without the master password, which they don’t have).

The query engine should have some kind of adaptive way of sensing specificity. It needs to have a way of seeing that the query provides only information about one person or a small subset. These queries would then be blocked. However, a blocked query is information in itself, so this isn’t a trivial problem.

Differential Privacy seems to make some progress on this front. The article linked above defines it as:

Imagine you have two otherwise identical databases, one with your information in it, and one without it. Differential Privacy ensures that the probability that a statistical query will produce a given result is (nearly) the same whether it’s conducted on the first or second database.

Its claims seem to fit the bill, but as I’m a bit mathematically disabled I can’t evaluate the claims fully. The idea of the budget is a bit of a concern as the point of this data store is to provide a queriable data set. It might be a big enough data set that the budget is essentially infinite. Maybe we could assume that multiple query makers will never collude to combine their results. (It seems likely that they would though.)

One way around the budget as a mathematical thing is to think of the data as permetual, but grant access via an ethics comittee. In the MichiganX: DS101x Data Science Ethics course16, in the lecture “limits on recording and use” at 6:09 there is a mention of how governments collect data. They don’t know what data they’ll need in the future, so they collect everything but aren’t allowed to look at it. They then get a warrant to access specific parts of it. This solves the budgetry constraints, but risks abuse by coordinated requests from different parties that could then combine their data to produce a specific outcome. There might be ways around this by doing things like indexing queries differenty so that it’s harder to combine different queries, but I’d imagine that this would provide little obstruction to a motivated nefarious actor.

Harms

What sorts of harms could be caused by this? Could harm be caused by collecting data or only by the use (abuse) of it afterwards?

There is also the effect caused by people changing their behaviours because of how they imagine that the data will be used, quite separate from how it is actually used. (A general distrust of what happens when the man gets data.)

Precedents

Carbon Buzz is a project that collects private data about building energy usage. The platform allows building owners/designers to upload their building performance data, and then to compare their building against the body of existing buildings. (Taking into account the type of building etc.) Organisations can be nervous about releasing this information publicly because it might show them up to be less competent than they’d like to present themselves as. The comparison can provide comparisons without specifics. E.g. you are better than 73% of other buildings in your category rather than saying you are better than x building and worse than y building.

A stab at a data format

It seems like a fairly straight forward time series data collection exercise, but there needs to be some sense of context. It’s not really useful if there is a person, in a place, at a time, if we know nothing about the context. My guess is that we’d need some kind of 3d representation of the space, more detail is better17. It would need recorded weather data and surrounding buildings for context. It may even need things like national mood to explain things working at different scales.

Here are some example scenarios for queries. These are just some ideas I had when I was having breakfast, there are many more and not all of these will be useful. All of them have methodological problems, they are more of a thought experiment than a suggestion.

-

Do office partition heights cause a sex bias?

Taller people can see over higher obstructions. Does this mean that some office furniture advantages taller people? As men tend to be taller, this disadvantage would fall disproportionally onto women? I’m not sure why this was the first thing that came to mind. This would need height, sex, movement data, some other factor to stand in for success, and at least two locations that had different furniture.

-

Do email, physical, IM etc. social networks correlate with each other?

Do people use different ways of communicating with different people? This seems intuitively true, but how? This would need access to the networks made by the communication platforms, and some people data to compare it to.

-

Do certain members of an organisation act as movement attractors/repellors? Is that correlated with anything else?

Do some people get pestered more than others? Will others cause people to alter their path through a space to avoid them? You could think of this as a prom queen and a teacher whose class deadline is approaching. You’d only need movement data. This may need to access quite granular data as you’d need to know if a single person was bending paths (rather than a class of people).

-

How late do meetings start and end?

Meetings have a cost and generate a value (ideally). My guess is that their value is only realised once certain people are in the room. The shoulder of the meeting are a loss of productivity. Movement data would let us know how much is lost.

-

Can movement patterns be generalised across spaces?

If we train some kind of simulation on movement data, does that generalise to a different space? E.g. if a company moves, can we use their previous data to predict movement patterns in the new space? (That’s a good way of controlling most other factors.)

-

Do designers’ intuitions about bump spaces match reality?

People run into each other and have impromptu meetings. Artificially encouraging this is a big selling point in many office designs. Do people bump where they are expected to?

-

What are occupancy percentages really? How does that vary? By sector? Role?

Occupancy percentages are usually given as a single figure for the whole space. (e.g. 45%) but that varies across teams, across the space itself, across time of day and year etc. Can this be expressed in a more nuanced way?

-

If we classify people based solely on movement behaviour? Does that match any other classification?

If we use an automatic classifier to segment a group of people just looking at their movement data, do those groups line up with any groups we already understand? Maybe we can say that “Men walk more than women” but maybe that is meaningless and there is a new way of dividing a population18.

-

If we can identify successful teams, does anything we measure correlate with that?

-

How do movement patterns change? What influences that?

-

What percentage of movement is universal and what is [org, sector, gender, geography, etc.] specific?

A stab at some kind of ethical framework

This is just me sketching to get the ball rolling. I’m sure that there are lots of bad edge cases wrapped up in here.

When I say individuals I mean the person being tracked, when I say organisations I mean whoever is doing the tracking.

- Individuals must be able to opt out19

- Individuals must have access to all the data that pertains specifically to them20

- Organisations must not be able to view or make decisions based on an individual’s data. The inability to query the data at an individual’s grain must also be unavailable to law enforcement, GCHQ, NSA etc.

- Organisations must be held accountable for any bad outcomes (whatever that means) that come from their use of the data. (horrible wording)

- The data must be queryable by everyone (public data)

- It must be possible to remove population bias from the data 21

-

I had a very nice Brazilian coffee from Square Mile roasters, he had a green tea. It sounds a bit strange to say “mixed hot drink meeting”. ↩

-

e.g.

-

There’s also a protectionist sense that anyone criticising the methodology must by definition be hostile and stopped. ↩

-

I know that things get messy when you get down to the level of quantum foam, and that weather is a probabilistic thing, but the sun will always be in a know position, and a certain number of photons falling on a certain material will behave in a very well defined way. ↩

-

Simple examples of simulation are structural analysis to see how a structure will be affected by loads:

fluid dynamics to see how things will fly or move through water:

or even ways of finding out how escapable an aircraft is

-

By committed I mean that there is a chance to change things before you are fully committed to a path. An example that comes to mind is the difference between a trebuchet and a cruise missile.

With a trebuchet you launch something into the air, see what happened and then adjust. There’s no way to nudge your rock left a bit if it’s off line. In the case of buildings, you’ve committed tens of millions to a 50 year trajectory with only minor adjustments possible. A simulation would mean that you are much more sure that you are pointing the rock in the right direction. Of course, changeable buildings would be even better (a la Google). ↩

-

I’m not saying negligent from a liability point of view, I’m suggesting that we’ll be judged harshly by history. There are plenty of things that were entirely legal to do at the time, but that we think of now as unacceptable. Usually this change in attitude preceded the legal change; this is what I’m hoping will happen here. ↩

-

one possible exception to the

shouldn’t harm any of the parties involved

idea might be that building designs that don’t work, or are objectively bad (whatever that means) could do reputational damage to their design teams. This might be a good thing because it would prevent people who introduce bad outcomes into the world would be selected against. It might go the other way though by making designers more risk averse (just copying an acceptable precedent) or by making developers looking to make cheap-and-bad buildings choose to stay out of the assessment protocol. ↩ -

I don’t have a reference for that, but I don’t think it’s likely to be disputed too much. ↩

-

I’m sure that there’s lots written about the peculiarities of peoples’ Facebook settings vs their feelings about nudist beaches.

E.g. Here’s how Pokemon Go gets full access to your Google account

I obviously don’t think Niantic are planning some global personal information heist. This is probably just the result of epic carelessness

and here’s another from the Washington Post reporting on a survey that claims that

45 percent said their concerns about online privacy and security stopped them from using the Web in very practical ways

. A lot of this seems to be because of general uncertainty around what it means to be secure these days. That said, a quick look through the comments shows a lot of people using the internet to complain about the internet—perhaps this is survivorship bias and there are lots of other people who’ve stopped using the internet all together. (I doubt it though.) ↩ -

A rational actor should be willing to endure some discomfort now (wearing a tracking device, knowing that they are being tracked) in exchange for a future pay off of having a much better life in the future. Humans are ‘bad’ at time discounting. (By bad I mean that they don’t behave like classical economics predicts that they will.) The future benefit needs to be sufficiently great, or the present discomfort sufficiently low, that people will do it for free. Otherwise they’ll need to be persuaded.

Another way to incentiveise would be if the user owned the data, and the organisations had to buy it off them. Maybe they get paid every time a query touched their records? but maybe the data will be biased as only people in need of money will take the money. Not being tracked would be a signal of status and wealth?

Gamification may be another lever. Gamification isn’t about points and badges and progress bars, it’s about increasing agency and the significance of choices, but also leveling up and beating people! The steps on a Fitbit are meaningful, users interpret them as micro units of fitness and wellbeing—negative micromorts.

Organisations could tip (after the fact) in accordance with the value they gained, but that’s ripe for freeriding. ↩

-

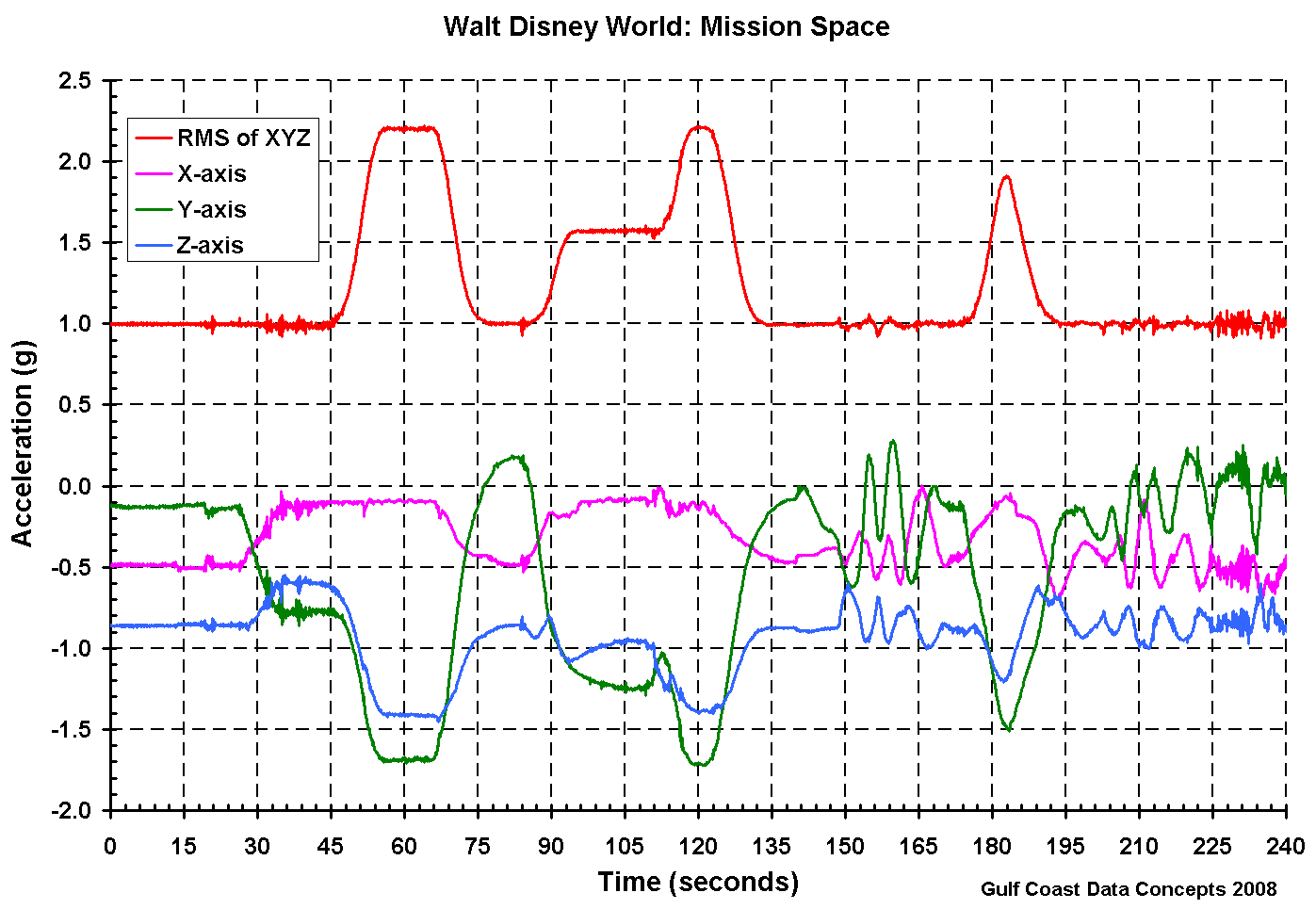

By data products I mean returning value to the user by deriving meaning from the data that have captured about them. It is probably easiest to go back to the Fitbit example.

Raw accelerometer data is of very little use to the majority of users. Fitbit processes the raw stream into things that the user cares about like steps or hours asleep. These sorts of things transfer value back to the user, and in fitbit’s case are valuable enough to get them to shell out $150 to buy a wristband. In other cases they might end up neutral (things like Google search, although I’d imagine that people might pay if they were asked to) or nett negative (but we don’t see that very often outside enterprise environments where people are forced to do these things. Even then they are being paid a salary, so you could claim that was payment enough. Examples of nett negative value transfers are hard to demonstrate because nobody would get into one!). ↩

Raw accelerometer data is of very little use to the majority of users. Fitbit processes the raw stream into things that the user cares about like steps or hours asleep. These sorts of things transfer value back to the user, and in fitbit’s case are valuable enough to get them to shell out $150 to buy a wristband. In other cases they might end up neutral (things like Google search, although I’d imagine that people might pay if they were asked to) or nett negative (but we don’t see that very often outside enterprise environments where people are forced to do these things. Even then they are being paid a salary, so you could claim that was payment enough. Examples of nett negative value transfers are hard to demonstrate because nobody would get into one!). ↩ -

I think that it’s important to record the building physics aspects of these things, but I’d prefer to not worry just now about creating a super-format that would allow for the recording of all building related time series data - but it might be necessary eventually! ↩

-

I wrote about this kind of thing here when I was doing some data collection work at BVN. ↩

-

From the article about differential-privacy that I previously linked to.

Unfortunately, even well-meaning data collection can go bad. For example, in the late 2000s, Netflix ran a competition to develop a better film recommendation algorithm. To drive the competition, they released an “anonymized” viewing dataset that had been stripped of identifying information. Unfortunately, this de-identification turned out to be insufficient. In a well-known piece of work, Narayanan and Shmatikov showed that such datasets could be used to re-identify specific users – and even predict their political affiliation! – if you simply knew a little bit of additional information about a given user.

-

I’m still looking for a reference to this concept. My guess is that it’s wrapped up in NSA type stuff ↩

-

It’s hard to know what too much detail looks like. We are influenced by such strange things. Although the field of priming is having a bit of a crisis at the moment it wouldn’t surprise me if things like floor covering affected peoples’ movements. I know I do things like walking along the edge of a shadow sometimes, perhaps that kind of effect is enough to be a factor? ↩

-

I don’t remember if it was Rayleigh or Cervelo, but a bike company did some ergonomic studies and found that women didn’t have different proportions to men (as the prevailing wisdom maintained) but that shorter people had different proportions to taller people. It was something that got into received wisdom through clumsy statistical analysis. ↩

-

While I think that everyone should be able to opt out, I think that it would be extremely poor form for anyone involved in building design to do so. I’d argue that they have a moral duty to do everything in their power to improve the quality of their output—as long as it’s not too arduous—and I don’t think that being tracked would count as being arduous.

Of course there is the potential for bad actors, so being able to opt out of that maintains the same intent as the right to bear arms, but without the undesirable outcomes. ↩

-

I’m not sure if people should be able to delete their past data. There is a network effect in the value of the data, and if the data can’t be queried to such a fine grain then there’s no way you could be caught in a broom cupboard with another staff member, so there’s no value to the individual in deleting the data. (Other than some perverse peace of mind.) ↩

-

I can see a potential problem here. If I want to simulate a building that contains only women I should be able to train on an all female data set. However I could also do an all men run and compare the results to produce a “ha, look how much better men are” headline. This might just be handled through existing experimental ethics. Also, context is going to be an issue here. For example, do men behave differently in all male environments? Is it valid to turn the gender bias all the way up when the data were sampled in a mixed environment. Don’t read too much into these examples, I just picked men and women as an obvious grouping, I realise that it’s more complicated! ↩