How Buildings Learn: Magazine Architecture

I found out about Steward Brand from his Long Now Foundation podcasts, and their project to make a 10 000 year clock. Quite separately I found out about How Buildings Learn, and only after reading it for a while did I realise that they were the same person. There aren’t many people with as much influence, across so many domains as Steward Brand.

Reading this chapter was an odd experience. It felt like I was being vindicated—my words, coming from someone respectable’s pen—I’m not a lone doomsayer. However, it also made me feel like I’ve wasted a lot of time, coming to these ideas by myself.

As a however by previous however, I doubt that if I’d read this 15 years ago it would have had any impact at all; I didn’t know nearly enough about the world for it to make any sense. This kind of knowledge needs a site for it to land.

Like I did with What Sort Of People Should there Be? by Jonathan Glover, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, I’ve copied this chapter out. I’ve been as accurate as I can, but if you spot an error then let me know. I’ve added some links to the references too.

CHAPTER 5

Magazine Architecture: No Road

Most buildings have neither High Road nor Low Road virtues. Instead they strenuously avoid any relationship whatever and what is considered its depredation. The very worst are famous new buildings, would-be famous buildings, imitation s buildings, and imitation imitation buildings. Whatever the error is, it is catching.

I first came to this question—and to this book—through experience with a building whose fame, as usual, is the fame of its architect. I. M. Pei was considered by a 1991 poll of the American Institute of Architects to be the most influential living American architect.” Designer of the glass pyramid and renovation for the Louvre in Paris and of a spectacular skyscraper in Hong Kong, his reputation is worldwide. The MIT campus in Massachusetts considers itself lucky to have three buildings designed by Pei, who was once a student there. In 1986 his third MIT building, known informally as the Media Lab and formally as the Wiesner Building, had just opened when I joined the Media Lab for a season as a visiting scientist. What I have to say about the building does not reflect on the people or the activities of the Media Laboratory itself, which I enjoyed so much I wrote a book about them.1

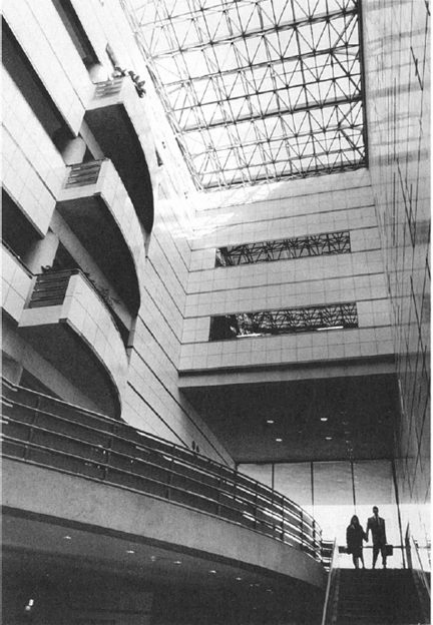

It may have been my familiarity with MIT’s homely, accommodating Building 20 just across the street that made the $45 million pretentiousness, ill-functionality, and non-adaptability of the Media Lab building so shocking to me. Here was a building purpose-built to house a diverse array of disciplines and people collaborating on deep research in fast-evolving computer and communication technologies. Consider in that light the building’s dominant feature-its vast, sterile atrium. In many research buildings a central atrium serves to bring people together with open stairways, casual meeting areas, and a shared entrance where everyone sees each other daily. The Media Lab’s atrium cuts people off from each other. There are three widely separated entrances (each huge and glassy), three elevators, few stairs, and from nowhere can you see other humans in the five-story-high space. Where people might be visible, they are carefully obscured by internal windows of smoked glass.

The atrium uses up so much of the building that actual working office and lab space is severely limited, making growth and new programs nearly impossible and exacerbating academic turf battles from the first day. Nowhere in the whole building is there a place for casual meetings, except for a tiny, overused kitchen. Corridors are narrow and barren. Getting new cabling through the interior concrete walls—a necessity in such a laboratory—requires bringing in jackhammers. You can’t even move office walls around, thanks to the overhead fluorescent lights being at a Pei-signature 45-degree angle to everything else.2

The Media Lab building, I discovered, is not unusually bad. Its badness is the norm in new buildings over designed by architects. How did architects come to be such an obstacle to adaptivity in buildings? That’s a central question not just for building users but for the architectural profession, which regards itself these years as being in crisis. Design professor C. Thomas Mitchell voices a common indictment:

A range of observers of architecture are now suggesting that the field may be bankrupt, the profession itself impotent, and the methods inapplicable to contemporary design tasks. It is further suggested that collectively they are incapable of producing pleasant, livable, and humane environments, except perhaps occasionally and then only by chance.3

20 November 1990. Brand.

1990 - Blessed with not one but two echoing lobbies, the Wiesner Building’s only cordial staircase links them. Foot traffic in all the working part of the building is forced to use depressing, hidden, concrete fire stairs. Researchers who are meant to collaborate across disciplines can go for weeks in the building without ever seeing each other casually. Desperate for more office and lab space, the Media Lab is considering tunnelling under the adjoining plaza.

20 November 1990. Brand.

1990 - Occupied in 1985, MIT Wiesner Building houses art galleries on the ground floor and The Media Laboratory in the basement and top three floors. The design of more convivial research buildings is not a mystery-see p. 172 (Mathematical Sciences Research Institute), p. 176 (MIT’s own Main Building) and p. 180 (Princeton’s Molecular Biology Laboratory).

IMPRESSIVE AND USELESS, the massive atrium in I. M. Pei’s Wiesner Building at MIT hogs space, isolates and overwhelms people, and provides no amenities. It was meant to be a work of art, a continuation of the building’s starkly Modernist skin (right) into the interior. The three balconies at upper left that look like truncated freeway exits serve no function whatever. The smoked-glass interior windows at upper right ensure that humans remain invisible in the space. The design may be alienating, but it’s expensive.

At the risk of sounding like yet another architect-basher, let me take a stab at diagnosis.

Marvin Minsky, one of the founders of Artificial Intelligence, was gazing across the deserted Media Lab atrium with me one day. The problem with architects,” he rasped, “is they think they’re artists, and they’re not very competent.”

Sure enough, if you look at the history of architecture as a profession, it was always around distinctions of art that architects distinguished themselves from mere builders”—starting in the mid-19th century, when the profession emerged, and continuing to the present day.4 “Art-and-Architecture” are always clumped together. What’s wrong with that? Few modern artists approve of anything static. Artistic architects should be the most accepting of all of interactivity with their audience.

The problems of art as architectural aspiration come down to these:

- Art is proudly non-functional and impractical.

- Art reveres the new and despises the conventional.

- Architectural art sells at a distance.

Architect Peter Calthorpe maintains that many of the follies of his profession would vanish if architects simply decided that what they do is craft instead of art. The distinction is fundamental, according to folklorist Henry Glassie: “If a pleasure-giving function predominates, the artefact is called art: if a practical function predominates, it is called craft.”5 Craft is something useful made with artfulness, with close attention to detail should buildings be.

Art must be inherently radical, but buildings are inherently conservative. Art must experiment to do its job. Most experiments fail Art costs extra. How much extra are you will to pay to live in a failed experiment? Art flouts convention Convention became conventional because it works. Aspiring to art means aspiring to a building that almost certainly cannot because the old good solutions are thrown away. The roof has dramatic new look, and it leaks dramatically.

Art begets fashion; fashion means style; style is made of illusion (granite veneer pretending to be solid; facade columns pretending to hold up something); and illusion is no friend to function. The fashion game is fun for architects to play and diverting for the public to watch, but it’s deadly for building users. When the height of fashion moves on, they’re the ones left behind, stuck in a building that was designed to look good rather than work well. and now it doesn’t even look good. They spend their day trapped in someone else’s taste, which everyone now agrees is bad taste Here, time becomes a problem for buildings. Fashion can only advance by punishing the no-longer-fashionable. Formerly stylish clothing you can throw or give away, a building goes on looking ever more out-of-it, decade after decade, until a new skin is grafted on at great expense, and the cycle begins again—months of glory, years of shame.

A major culprit is architectural photography, according to a group of Architecture Department faculty I had lunch with at the University of California, Berkeley. Clare Cooper Marcus said it most clearly: “You get work through getting awards, and the award system is based on photographs. Not use. Not context. Just purely visual photographs taken before people start using the building.” Tales were told of ambitious architects specifically performing well designing their buildings to photograph well at the expense of performing well.

I heard something similar from San Francisco architect Herb Mclaughlin: “Awards never reflect functionality. I remember serving on a jury one time and suggesting, ‘Okay, we’ve winnowed this down to ten projects that we really like. Let’s call the clients and see how they feel about the buildings, because I don’t want to give an award to a building that doesn’t work. I was hooted down by my fellow architects.” In London, architect Frank Duffy fumed to me about the curse of architectural photography, which is all about the wonderfully composed shot, the absolutely lifeless picture that takes time out of architecture—the photograph taken the day before move-in. That’s what you get awards for, that’s what you make a career based on. All those lovely but empty stills of uninhabited and uninhabitable spaces have squeezed more life out of architecture than perhaps any other single factor.”

At a building preservation conference in Charleston, South Carolina, I chatted with an architecture student. Interested primarily in rehab and restoration work, she referred unflatteringly to the majority of her 450 fellow students at the Tulane University Architecture Department as “magazine architects.” By which she meant image-driven and fad-driven architecture, because architecture magazines probe no deeper than the look and style of the buildings they cover. They never interview clients or users. They never criticize buildings except, rarely, in terms of being bad art or off-trend. Articles consist primarily of stylized color photographs. Reports cover only new or newly renovated buildings, often in language that sounds like the prismatic luminescence” school of wine writing. The subject is taste, not use; commercial success, not operational success. Architecture magazines are about what sells. They are advertising, cover to cover.

13 June 1993. Brand.

1993 - Ashlar, with its vertical and horizontal joints, is the most prestigious of masonry techniques. Arycanda is sited on the steep face of a mountain. This was a retaining wall behind the stadium seating. The stones are massive.

FAKE ASHLAR ON REAL ASHLAR. The illusion of perfectly dressed stone was incised in stucco over very well-dressed genuine stone at the Classical Greek stadium (4th century B.C.) at Arycanda in modern Turkey. Through the ages, style-conscious building designers have preferred faux materials to the real thing. Early Modernist theory sneered at such fakery, but later Modernist architects were eager to clad their boxes with phoney veneers.

Architecture, being art, is supposed to have movements. In the customary sequence, a movement starts in relevance, loses it but prospers anyway for many years, then succumbs to the next cycle. Modernism began in the 1890s with the arrival of whole new kinds of buildings-factories, department stores, high rises. Form, stuck for precedent, followed function. Then that insight was aestheticized (and anesthetized) by the Bauhaus movement in the 1920s and 1930s, and its teachers migrated to America to avoid Hitler. So matters stood when all of America and Europe needed new buildings after the war-America to express its new prowess and prosperity, Europe to replace its devastated cities. Modernism got renamed the International Style (“because no one wanted to claim it,” says Boston city planner Stephen Coyle), and suddenly all the world’s major cities began to look the same. Being minimalist on principle, Modernist buildings could be built cheap but showy. Less money for construction, more glory for the architect. Everybody won but the users.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, architecture departments on a few campuses such as MIT, Berkeley, and London’s Architectural Association fomented a revolution in response to the painfully evident failures of Modernism. Teachers began to talk of the need for “loose fit” in designing buildings, so that unexpected uses of the building could be accommodate6 “Post-Occupancy Evaluation” was invented and became a subdiscipline. Chris Alexander and colleagues came up with their “pattern language” of design elements that wear well. The rapid growth of services such as air-conditioning led to more systemic study of buildings and their uses. Conserving energy became a source of design innovation. Even the psychology of building use was explored. Then it all faded. What happened?

Art fought back. In 1966 the Museum of Modern Art had published a book by architect Robert Venturi titled Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. It attacked the puritanical simplicity of Modernism—“I am for messy vitality over obvious unity.” In 1972 Venturi aesthetically interpreted a commercial event—the gaudy success in Las Vegas of what he called decorated sheds.”7 The insight was perfect. Now architects could celebrate the corner they had been backed into by the fragmentation of the building trades, and be exterior decorators solely and proudly. I don’t fault Venturi; I admire his buildings and writings. It was the leadership of the profession that took the easy path away from complex responsibility and back to airy debate about style.

By the 1980s, “Post-Modernism” had swept the architecture departments and the rising partnerships. “Historicism—casual looting of historic styles—took off, and Palladian half-circles triangular gable ends and toy-like cheery colors bedizened the land. To their credit, Postmodern buildings were general purpose and adaptive inside—decorated sheds.

But their appeal was shallow. Architect Peter Calthorpe say if architecture suffered a stroke after World War II, lost its language and intelligence, and couldn’t articulate real buildings any more, so it just made boxes. With Post-Modernism, the profession was finally beginning to manage a few words again but it still couldn’t handle sentences or paragraphs. Instead of settling down to real homework, the Post-Modern movement increasingly fragmented into shards of self-consciousness. Obsession with such distractions as French literary criticism culminated with a suicide dive into blatantly “postfunctional” Deconstructionism.

By the early 1990s architecture was adrift—toying with Neo-Modernism, Late Modernism, Second Modernity, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Rationalism, and other signs of being open to renewed investigations of relevance. In an essay titled For an Architecture of Reality architect Michael Benedikt reminded his colleagues, We count upon our buildings to form the stable matrix of our lives, to protect us, to stand up to us, to give us addresses, and not to be made of mirrors.”8

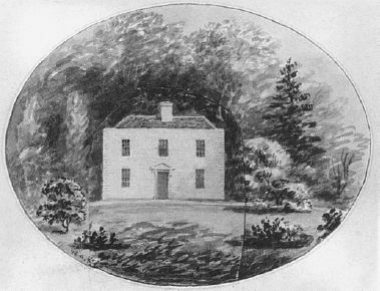

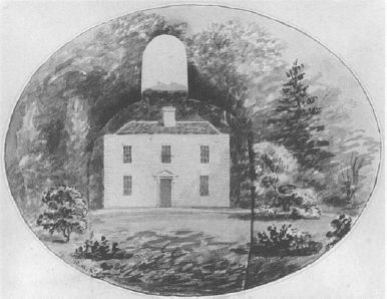

From Repton’s beautiful “Red Book” at the British Architectural Library. Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Neg No 0272

“FACADECTOMY” is no recent phenomenon. Eighteenth century architect and landscape gardener Humphrey Repton (1752-1818) offered the service to his clients with clever watercolor renderings. The viewer untabbed and lowered the flap to reveal the new look in the old setting.

A building’s exterior is a strange thing to concentrate on anyway. All that effort goes into impressing the wrong people—passers-by instead of the people who use the building. Only if there is a heavily trafficked courtyard or garden do the building dwellers notice the exterior at all after the first few days. Most often the don’t even enter by way of the facade and big lobby; they come in by the garage door. And yet, ever since the Renaissance, “the history of architecture is the history of facades.” It is a massive misdirection of money and design effort, considering how badly buildings need their fundamentals taken care of. Chris Alexander is vehement: “Our present attitude is all reversed. What you have is extremely expensive structure and all this glitz on the surface The structure rots after thirty years, and the glitz is so expensive that you daren’t even fuck with it.”

Architects got themselves stuck in the skin trade. Frank Duffy observes, “The only area of architectural discretion in artistic or financial terms is the skin. The architectural imagination has allowed itself to be well and truly marginalized.9 It happened because architects offered themselves as providers of instant solutions, and only the look of a building gives instant gratification. When the space planning doesn’t work out and needs improvement, or the structure indeed rots, where’s the architect Long gone.

There is little public accounting. The celebrated British architectural triumvirate of the 1980s the late James Stirling, Norman Foster, and Richard Rogers Shared equal reputations even though Foster’s buildings were routinely competent while Stirling’s and Rogers’s, in my view, had serious problems. Stirling’s history Faculty building at Cambridge (1967) leaked badly, kept dropping terra cotta tiles on the students, and faced the wrong way, so the sun cooked its contents—people books. Pompidou Centre (1979) in Paris, co-designed by Rogers, requires prodigious amounts of maintenance. His Lloyd’s tower in London (1985) was extraordinarily expensive, yet in 1988 three fourths of its occupants said they preferred their former building.10 Reputations based on exterior originality miss everything important. They have nothing to do with what buildings do all day and almost nothing to do with what architects do all day.

Does the building manage to keep the rain out? That’s a core issue seldom mentioned in the magazines but incessantly mentioned by building users, usually through clenched teeth. They can’t believe it when their expensive new building, perhaps by a famous architect, crafted with up-to-the-minute high-tech materials, leaks. The flat roof leaks, the parapets leak, the Modernist right angle between roof and wall leaks, the numerous service penetrations through the roof leak; the wall itself, made of a single layer of snazzy new material and without benefit of roof overhang, leaks. In the 1980s, 80 percent of the ever-growing post construction claims against architects were for leaks.

Architects’ reputations should rot if their buildings can’t handle rain. Frank Lloyd Wright was chosen by a poll of the American Institute of Architects as “the greatest American architect of all time.” They all knew his damp secret:

Leaks are a given in any Wright house. Indeed, the architect has been notorious not only for his leaks but for his flippant dismissals of client complaints. He reportedly asserted that, “If the roof doesn’t leak, the architect hasn’t been creative enough.” His stock response to clients who complained of leaking roofs was, “That’s how you can tell it’s a roof.”11

Wright’s late-in-life triumph, Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, celebrated by the AIA poll as the best all-time work of American architecture,” lives up to its name with a plague of leaks, they have marred the windows and stone walls and deteriorated the structural concrete. To its original owner, Fallingwater was known as “Rising Mildew,” a “seven-bucket building.” It is indeed a gorgeous and influential house, but unlivable. For its leaks there can be no excuse.

Wright is an interesting study of a superstar architect having both right and wrong influence. “All Architecture, worthy the name”, he decreed in 1910, “will, henceforward, more and more be organic.”12 So inspired by Viollet-le-Duc and Louis Sullivan inspired countless others (including young me) toward an organic approach to architecture. At the same time, the very pomposity his decrees helped inflame a fatal egotism in generations of architects, and his most famous buildings belie his organic ideal They were so totally designed—down to the screwheads all being aligned horizontally to match his prairie line—that they cannot he changed. To live in one of his houses is to be the curator of a Frank Lloyd Wright museum: don’t even think of altering anything the master touched. They are not living homes but petrified art, organic only in idea, stillborn.

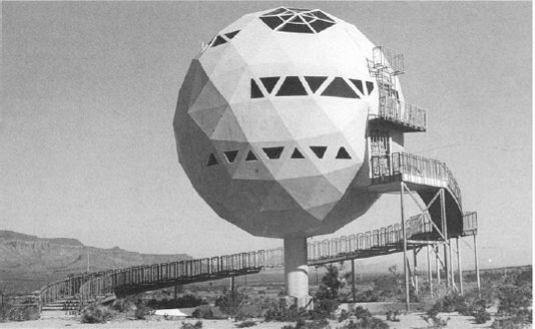

June 1988. ©Lloyd Kahn.

1988 - Though it was competently built by Bill Woods of Dyna Domes, Phoenix, soundness and sheer flash were not enough to keep so unwieldy a space occupied.

ABANDONED DOME. A combination restaurant, bar, and real estate office, this geodesic dome stands empty by the highway near Yucca, Arizona. How would one add to it? The difficulty of dealing with a curved exterior is apparent in the stairs/fire escape grappling to reach three floors. Inside is even more awkward. It is an amazing structure to look at, though.

A large part of Wright’s problem with exasperated clients (and with rain) can be traced to his impatience with the traditional rectangular shape of buildings. “I have, lifelong, been fighting the pull of the specious old box,” he told the AIA in 1952,13 and too many listened. Architects love exotic building shapes. Wright was always experimenting with hexagonal, triangular, and round shapes in his structures. They were impressive, but they fought the hand of dwellers as well as builders. Wright didn’t care. I. M. Pei has shown similar obliviousness in such buildings as the highly admired, severely triangular East Wing of the National Gallery in Washington, DC. Every space in the building is a pain to work with. Even the shelves in the voluminous library end in acute or obtuse angles that won’t hold a book; special, space wasting blocks, different for each shelf end, had to be fashioned. The crowning indulgence was a triangular elevator, gratuitously awkward, astronomically expensive.

As for domes, fancied by architects through the ages, the findings are now in, based on an entire generation experience with Buckminster Fuller geodesic domes in the 1970s. They were much touted in the architecture magazines of the period. As a major propagandist for Fuller domes in my Whole Earth Catalogue, I can report with mixed chagrin and glee that they were a massive, total failure. Count the ways…

Domes leaked, always. The angles between the facets could never be sealed successfully. If you gave up and tried to shingle the whole damn thing—dangerous process, ugly result—the nearly horizontal shingles on top still took in water. The inside was basically one big room, impossible to subdivide, with too much space wasted up high. The shape made it a whispering gallery that broadcast private sounds to everyone in the dome. Construction was a nightmare because everything was non-standard—“Contractors who have worked on domes all swear that they’ll never do another.”14 Even the vaunted advantage of saving on materials with a dome didn’t work out, because cutting triangles and pentagons from rectangular sheets of plywood left enormous waste. Insulating was a huge hassle. Doors and windows weakened the structure, and they leaked because of shape and angle problems.

Worst of all, domes couldn’t grow or adapt. Redefining space inside was difficult, adding anything to the outside nearly impossible—a cut-and-try process of matching compound angles and curves. When my generation outgrew the domes, we simply left them empty, like hatchlings leaving their eggshells.

We didn’t know it at the time, but the Fuller dome craze was a reprise of an earlier American architectural folly. In 1849 a phrenologist named Orson Fowler published a book titled A Home for All,15 which lauded the benefits of octagon-shaped houses. A minor rage for building the things swept America. Only a few survive. Like domes, they proved awkward to subdivide or add to, and the fad was self-extinguishing. Fowler eventually moved out of his own octagon. When he built again in 1877, it was a conventional house. (Neither Fowler nor Fuller, it must be noted, were architects.)

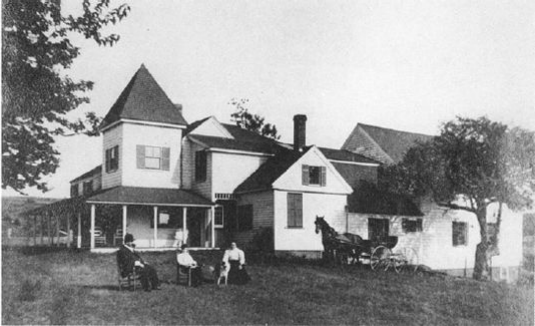

HABS. Library of Congress. Neg. No.316863

ca 1890 - This amalgam near Truro, Massachusetts, was recently reduced by a Cape Cod purist to just the original house and an ell. What is added to a rectangular building can be subtracted fairly gracefully.

THE OPPOSITE OF A DOME in eve respect is a plain old rectangular Cape Cod house. Nearly hidden behind additions, the original house here (1825) is at the left rear. Right angles flat walls, and simple roofs made it easy to add a tower, a wraparound porch, a two-story lean-to, a kitchen el (with narrow stove chimney), and a one-story lean-to connecting to the barn at the right. The add-on look of “cascading roofs” is currently much imitated in brand new houses. (Too bad. It makes them expensive and hard to add on to. Leaping at the look prevents the reality.)

Architects perpetually seeking a radical new look should study the lessons of domes. Dome apostate Lloyd Kahn rediscovered verticality: “What’s good about 90-degree walls: they don’t catch dust, rain doesn’t sit on them, easy to add to; gravity, not tension, holds them in place. It’s easy to build in counters, shelves, arrange furniture, bathtubs, beds. We are 90 degrees to the earth.”16 Occupants are always intuitively oriented in rectangular buildings. (Orientation itself is a right-angle concept, the car directions being at 90 degrees. Since buildings inevitably grow is handy to have the five directions (including up) that rectangular buildings offer for expansion. Right-angled shapes nest and with each other universally, so tables fit into corners, and clothes into closets, and buildings into city lots, and lots into city blocks. Humanity’s first cities in Sumer had rectangular street grids. Tribal cultures the world over have beautiful round dwellings, but the shape of civilization is rectangular. The “specious old box” is old because it is profoundly adaptive.

But it’s not just because of impractical designs that architects are aly involved in 5 percent of new buildings. The architect is being marginalized by the pathological fragmentation of the professions and trades. Is the architect a generalist, a maker of buildings, or a specialist, a mere artist? That question unts the profession, because students are attracted to architecture as a wondrous calling for great souls guiding huge projects with all-embracing talent and skill, After graduation they encounter a tawdry reality-architect as deskilled and disempowered minor player who is increasingly left out entirely. A standard commercial building project is set in motion by a speculator (who may not plan to be the landlord) contracting with an architectural office for a building design. The design goes through a gauntlet of permits and emerges distorted, if at all. At this point the work is handed over to a battery of engineers- structural, service, “value,” etc.-who have been trained to a completely different discipline than the architect and who are scrupulously shielded from any skill or interest in aesthetic design. Then responsibility shifts to a general contractor, with the architect now reduced to an observational rather than supervisory role. The contractor passes 80 percent of the work to subcontractors.

They are often the ones with the cutting-edge technical skills, but they are too far downstream to affect design. Once the building is finished, it is turned over to facilities managers who will actually run the building. They of course have had no hand in its design. The speculator sells to a landlord, who rents to tenants, whose sole design function is to pay retroactively for the whole mess. The result? The British editor of this book, Ravi Mirchandani, has a tale identical to what I encountered in a dozen other publishing offices in London and New York: “Penguin’s building is too hot in the winter and too cold in the summer. The air is stale; everyone has colds that are endless. No one likes the building, and it’s only five or six years old. Nobody knows the designer’s name-just some team who retreated into the shadows.”

The process has evolved in part to disperse responsibility and foil lawsuits. It fails in that respect too. Lawsuits increase yearly. So far, two partial solutions to the fragmentation problem have emerged, one characteristically Japanese, one pragmatically American.

Japan has turned a cohesive design-build approach into mega success with a half dozen multi-billion-dollar firms like Kajima and Obayashi, capable of building whole cities. Employing Japanese traditions of collaboration and long-term commitment, these companies offer one-stop-shop, cradle-to-grave service. From one closely coordinated group you get financing, site selection, building design, construction, interior design, furnishings, facilities management, and maintenance. The designers and facilities managers have to listen to each other, because they work for the same company. The client (often the tenant) can complain to one person in the system and expect timely correction. Japanese custom discourages lawsuits and encourages reality-based accommodation Architecture, treated as a craft rather than an art, is taught in engineering departments. The Japanese design-build methodology has developed to such efficiency that some highrises have construction begun on their base before the top is completely designed-“just-in-time” design.”17 Research & Development gets ten times what American firms spend. In the international market these companies are often murdering American and European competition. And their buildings don’t leak.

The American solution is much more combative. Here the illuminating book is Joel Garreau Edge City, which describes the teeming new commercial complexes arising around the periphery of cities:

The height, shape, size, density, orientation, and materials of most buildings are largely determined by the formulaic economics of the Deal. It was stunning how completely it was the developers who turned out to be our master city builders. The developers were the ones who envisioned the projects, acquired the land, exercised the planning, got the money, hired the architects if there were any, lined up the builders, and managed the project to completion. Often, it was the developers who continued to manage and maintain the buildings afterward… Architects were lucky if they got to choose the skin of the building.18

The combat between architects and developers was decided some while ago. Architects are a minor ornament of the culture. Developers build America. There are countless departments and schools of architecture, but the only training for developers is deep within a few business schools. Most development is simply done by whoever has the money and the nerve and the ability to make people collaborate. Because developers are truly driven by the market, there is a rowdy but honest market feedback in the system. What doesn’t work, they blithely tear down or remodel until it does work. Architects are too lofty to study what is going on until a peer like Robert Venturi declares, “Learn from Las Vegas;” and “Main Street is almost all right;” and “Developers build for markets rather than for Man and probably do less harm than authoritarian architects would do if they had the developers’ power.”19

Fragmentation envelops the customer as well. Clients often are no better at representing building users than architects are. Usually a building is so large and complex an undertaking that the “stakeholders” are too diverse, scattered, and at odds to agree on much of anything. Architects complain justifiably that client organizations typically bump “facilities” decisions and supervision down to about the third layer of management, where decisiveness and clarity are scarce. Sometimes the company’s single most knowledgeable person about what is happening with the projected building is the lawyer hired to supervise all the multidirectional negotiations and agreements. Major design decisions wind up being made semi-randomly by the lawyer because no one is crisply in charge.

Another misdirection comes from the way architects and contractors are paid. The standard fee for an architect is around 10 percent of the building cost (6-7 percent for a commercial building). That’s about right for the amount of work it takes, but it introduces a pernicious incentive. The client asks, “What if we added another bed and bath over here?” The architect says. “It might come to $50,000 extra”—thinking, another $5,000 for me. An unethical architect would remark, “It could be very nice on that side of the house,” instead of advising, “You really don’t need it, and you could add it later, especially if we design this wall here with that in mind.” The percent approach is a conflict of interest for the architect; it encourages buildings that try to be too perfect and too large too soon. Better would be to agree with the architect in advance on a set budget and set fee for the building. with a significant bonus for the architect if the project stays within the budget.

However, an unscrupulous contractor can undermine that approach in a hurry. Construction costs get really corrupt in the area of “claims” arising from “change orders.” Changes that come up during construction are billed punitively by the contractor Frank Duffy is savage on the subject: “It’s a racket. It’s disgraceful If you are a British contractor, the biggest department you will have is called ‘Claims,’ where modifications are costed and invoiced. You will have your best intelligence working in claims.

It is a major industry, more important than building buildings. It is all based on the idea that only the client changes his mind. The building industry is a timeless and perfect automaton that exists owIn Claims the only to carry out specific instructions. It doesn’t have a mind of its timeful is being negotiation in Claims the boundary between the timeless and the is being negotiated-that’s why it’s such a hot issue. It’s mic. It leads to agony for the client and money for the contractor. It’s very destructive; that’s why it’s so evil. It’s also evil because it’s stupid, it denies intelligence.”

What is punished by claims is any kind of adaptivity during construction—exactly the time when you most want it, because the building is incomplete enough to fix and improve easily. Also that’s when you can take advantage of the skills and intelligence of the artisans to fine-tune design solutions on the site.

The simultaneous seizing of power and shedding of responsibility by contractors puts the onus on architects to anticipate perfectly all of a building’s needs. Nothing is left to the builders, to the client, or to actual usage. But if architects are now in a bind with that, they asked for it. They sought total control and promised total prescience. Frank Duffy: “Inherent to the Modern movement is the German idea of gestalt totality. It’s Bauhaus. It’s a terribly powerful word that was interpreted by architects as the power to determine every detail of the building. And you cannot touch anything once it’s there.” Architects of this persuasion want your light switches and toilet stalls, desks and fire stairs to reflect the same pervasive aesthetic as the roof line and lobby. Of your life is out of synch with that, too bad.

Gestalt design defies what should have been learned from the history-of-architecture courses (which were optional for architecture students in the Modernist years but now are required again). The most admired of old buildings, such as the Gothic palazzos of Venice, are time-drenched. The republic that lasted 800 years celebrated duration in its buildings by swirling together over time a kaleidoscope of periods and cultural styles all patched together in layers of mismatched fragments an aesthetic practice that may be appropriate to our own multicultural age.

Instead of steady accumulation, the business of contemporary architecture is dominated by two instants in time. One is the moment of go-ahead, when the architect’s reputation and the beguiling qualities of the renderings and model of the building to-be overwhelm the client’s resistance. The other is the moment of hand-over, when the building shifts from the responsibility of the builders to the responsibility of the owner, and occupancy begins. These are necessary moments to make coordination possible, but they distort everything. Each instant is a massive barrier to learning.

The effort is to make everything perfect and final for each of these opening nights. The finished-looking model and visually obsessive renderings dominate the let’s-do-it meeting, so that shallow guesses are frozen as deep decisions. All the design intelligence gets forced to the earliest part of the building process, when everyone knows the least about what is really needed. “A lot of the time now, you see buildings that look exactly like their models,” one model maker told me. “That’s when you know you’re in trouble.”

Chris Alexander likes to make on-site adjustment to a building as it’s being constructed. “Architects are supposed to be good visualizers, and we are,” he says, “but still, most of the time we’re wrong. Even when you build the things yourself and you’re doing good, you’re still making nine mistakes for every success. So you take the time to correct them. The more at each stage you can approach being able to experience the contemplated reality, the more it will give you feedback and you’ll be able to intelligently develop it.”

National Trust for Historic Preservation. Hardy Holtzman Pfeiffer Associates.

Hugh Hardy. Hardy Holtzman Pfeiffer Associates.

©Cervin Robinson. These photos appeared in Old & New Architecture (Washington: Preservation Press), pp. 260–261

URBANE MEMORY. On March 6, 1970, political activists (the Weathermen) accidently blew up themselves and an 1840s row house in New York. Architect Hugh Hardy designed a replacement that fit in politely with the neighbor buildings but also acknowledged what had happened on the site.

The time to correct mistakes is not available, shout the architects, the contractors, the bankers, and the clients. Right, groans Alexander, and that’s why most buildings are crappy. “There is real misunderstanding about whether buildings are something dynamic or something static. The architect has such a narrow niche. Anything different from the idea that you make a set of drawings and someone else builds the thing is incredibly threatening. People get just absolutely freaked out. I think it’s because it raises specters about contracts.” Matisse Enzer, a contractor who has worked with Alexander, agrees: “Architects think of a building as a complete thing, while builders think of it and know it as a sequence-hole, then foundation, framing, roof, etc. The separation of design from making has resulted in a built environment that has no ‘flow’ to it-you simply cannot design an improvisation or an adaptation. It’s dead.”

Then comes the barrier of occupancy. A kind of frenzy grips the job site as contractor, client, and architect grind their way da down the “punch list” that defines all the details to be finished before job is done. The heroic joys of framing are long forgotten; now the finishing drags on and on, with querulous subcontractors gaps between responsibilities, and scheduling hassles that make delays avalanche. Tempers snap, lawyers circle, and everyone just wants the nightmare to end. It ends in exhaustion. The building’s users, makers, and designers want nothing to do with each other ever again.

The race for finality undermines the whole process. In reality, finishing is never finished, but the building is designed and constructed with fiendish thoroughness to deny that. The occupants are supposed to march in and gratefully do exactly what it was declared they would do two years before, during the design stage, and the building will punish them if they don’t.

Landscape architects don’t think that way. They know that what they design has its own life, and they plan accordingly. One of the greatest was “Capability” Brown, whose 18th century work in England is lauded by Deborah Devonshire, based on her experience with Brown’s park at Chatsworth: “Brown planted the wood in wedge-shaped compartments, so when one section is mature and ready to be felled, another is growing and the line remains unbroken…. Brown’s gift of foresight and his ability to picture how the scenery would look 200 years after he finished his work is evident in parks in nearly every county in England.”20 Neither do space planners think about finality. Frank Duffy recalls ha experience that turned him away from standard architecture in 1960s in New York City: “The space planners-sort of sub architects-got a million things right that we hadn’t. They understood time. They worked for the IBMs and the Salomon Brothers, who were always changing, and they invented a design service which was related to change in a totally unglamorous, very New York, pragmatic sort of way. Few architects got involved; it came out of the commercial-interiors world. Philip Johnson, I remember, called them ‘hacks’-no significance at all. But they got it right. That’s where I learnt the insight. I was a consultant to them. I did a post-occupancy evaluation for Arthur Andersen in New York in 1968, which must have been one of the first POES ever done.”

The inane but now standard term “post-occupancy evaluation” (POE) shows what a divisive watershed the moment of occupancy is. One of architecture’s most adaptive devices is misnamed by the traumatic instant of letting users into a building. Why not just “use-evaluation,” since that’s what it is?

POEs are a shockingly direct procedure for judging how well a building works by formally surveying the occupants, especially the people who clean, service, or repair the building and know its failures all too well. Trained observers also watch and photograph how the building is used, comparing what actually is happening against what was intended. POEs began as recently as 1967, with a study of highrise student dormitories at the University of California, Berkeley. The study showed that large, showy lounges and recreation rooms were seldom used, that students were frantic for quiet and privacy to study in, that student rooms and desks were way too small, and that the rooms could not even be decorated by their reluctant occupants. Student were fleeing the dorms for any kind of private apartment or shared house in Berkeley. The design of dormitories improved as a result of the study.21

Herbert McLaughlin, head of KMD, San Francisco’s largest architectural firm, has thought about how POES could work optimally: “We believe you should go back three times. You should do it with the people who are going to use the building six weeks before it opens, to record their expectations. That gives you a very interesting base. You should go back within the first six months, when they’re still fresh on the place and really feeling all the uneasy elements. Then you should go back about two years later, after they’ve accommodated themselves to the building. It would be wonderful to do a fourth one maybe ten years later, because by then the world has changed. Has your building been able to accommodate that change?” Such a sequence would measure expectation, initial frustration and delight, adjustment, and long-term adaptivity. It’s never been done. The few POEs that do get done are mostly hidden. Architecture magazine explains why:

Architects generally have been slow to join the evaluation bandwagon. More often than not, the pull to conduct evaluations has come from client organizations, not from the architects themselves. Many architects in the past have regarded POE as negative feedback… Organizations willing to pay for POEs tend to develop buildings of the same type on a regular basis and are interested in perfecting the end result… Much of the private evaluation work done is proprietary. Organizations such as Marriot, McDonald’s, IBM, Steelcase, and Red Lobster all perform POEs in some fashion, but the results rarely are published.22

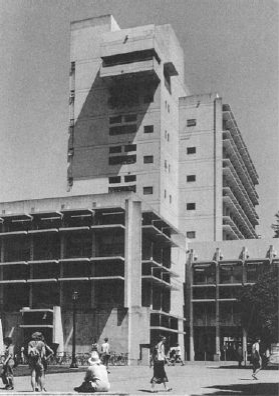

Friday mid-afternoon 16 August 1991. Brand.

1991 - Excessive high rise glass, as in New Zealand House, is a many-leveled error it punishes the occupants perpetually, it advertises its folly to the public, and it is prohibitively expensive to correct. The building’s curtains track the sun like a negative sunflower.

“THE SINS OF THE ARCHITECT are permanent sins,” wrote Frank Lloyd Wright. London’s sore-thumb highrise, New Zealand House, has glass curtain walls that force the occupants to pull reflective curtains whenever the sun comes out, or bake. So much for the view.

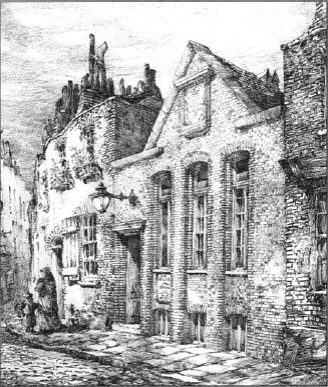

British Architectural Library. Royal Institute of British Architects.

ca. 1891 - Pite’s mission was on Old Montague Street, Whitechapel. None of the buildings survived re-development

ANTICIPATING TIME (right), architect Arthur Beresford Pite (1861-1934) rendered his new mission hall as if it was already old, to blend in with London’s East Fed slums around it. The practice is so rare as to be collectible.

I recall asking one architect what he learned from his earlier buildings. “Oh, you never go back!” he exclaimed, “It’s too discouraging.” That answer inspired this chapter. In a remarkable study of fifty-eight new business buildings near London, researchers found that in only one case in ten did the architect ever return to the building-and then with no interest in evaluation. The facilities managers interviewed for the study had universally acid views about the architects. One said, “Their primary interest is in aesthetics rather than practicality; it is a ludicrous situation. It’s no good if the building looks nice and doesn’t work.” Another: “They design it and move on to the next one. They’re paid their fee and don’t want to know.”23

Frank Duffy regrets what has happened to post-occupancy evaluation since he started with it in 1968. “It’s got somewhat trapped in the academic field, I’m afraid,” he said. Architects seldom get around to it. “The fundamental reason is the difficulty of putting buildings up is so great, and the pressures of getting it right on the night are so enormous, that squeezes out concern for the user and it squeezes out concern for time. I think architects have a tremendous responsibility for change here, because we ought to be the gateway between the construction and the consumer.”

His view is supported by a growing practice in the industry of hiring “project managers” instead of architects to run the construction process. According to one book, “The construction management sector did not exist in 1967. but today its dollar volume rivals that of architectural firms.”24 This is a classic case of an overly self-protective profession being steadily displaced by paraprofessionals. Architects must widen their skill sets or continue dwindling into resented irrelevance.

It may be difficult. Architects and their profession are constitutionally resistant to learning. The restoration specialist food architect) William Seale gives historical perspective: “I have a theory about architects. In France in the 19th century, when all our boys went over there and studied architecture, a professional architect was a man with a job and a salary, usually assigned to one great building. Architects now have all this schooling. They have to run a business when they get out of school or starve, and it’s a starvation business to be in, because the overhead is consuming, and sometimes the wave just gets them. They spend the rest of their careers peddling what they learned in school. Most architects I know are hustling their tails to survive. They don’t have the time to enrich themselves, to learn. They’re too busy to grow. I think a creative person has to constantly grow, or forget it.”

How close to the edge are architects? In the recession of the early 1970s, half of New York’s architectural firms went out of business.25 The combination of recession and a real-estate collapse in the early 1990s was even more brutal nationwide. It is in the nature of hustling for a living that the hustler must always focus on the next job, giving just enough attention to current jobs to get by, and no attention at all to past jobs. Two famed California architects, Bernard Maybeck and Charles Greene (of Greene and Greene), overcame the discontinuity problem by performing constant experiments on their own homes. Those houses became showcases, not of some finished theory, but of lifelong never-finished learning. A walk through their houses was said to be like a walk through the history of their creative development. The instance is noteworthy because it is rare.

One corrective has emerged. In the 1980s, malpractice lawsuits against architects surpassed those against doctors. Architects are learning painfully in court what they did not learn in school or from their buildings about leaky roofs, feeble structure, shoddy materials, poor detailing, inept window design. The same harsh lessons are driven in by the providers of their expensive “errors and omissions” insurance. Distinct improvement in the profession has resulted. So have some evasive techniques, such as grouping the designers of a public building together in a shallow corporation that conveniently dies when the lawsuits begin.

Greene & Greene Library. The Gamble House. USC.

1903 - The house at 400 Arroyo View Drive in Pasadena was designed by Greene & Greene as a two-story rental for a real estate speculator.

©Marvin Rand. Greene & Greene Library. The Gamble House. USC. These photos appear in a delightful book Greene & Greene by Randell L. Makinson (Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith, 1977) pp. 75 and 140.

1908 - James W. Neill bought the house for a residence and invited the Greene To exercise their growing craft. They nailed shingles over the clapboard siding, expanded the living room to include the side porch, ed a front porch, a brick-and-boulder buttressed terrace, and a pergola over the drive.

GOING BACK to an earlier building can be one of the great treats, both for architect and client. As their Craftsman style and technique improved from year to year, California’s Charles and Henry Greene were often invited back to upgrade prior houses. They learned what features wore well with time and what turned out to be mistakes, and they got to fix them. This bungalow in Pasadena went from a low-budget rental unit to a prime home.

Legal action is a hugely inefficient method of failure analysis. To decrease costs and vulnerability, architects-individually and as a profession-would do well to explore other means. Something “architect Richard Boone and his colleagues in the Office very specific of this sort has been set up in New York State, where General Services… have developed a database on roof design and performance. The database tracks a growing number of 10,000 buildings, recording variables of location, design state’s conditions, specified components, testing results, and the ults, and the history of problems and their solutions. By correlating design information with performance problems, the architects identify patterns success and failure. “26 How interesting it would be to go eu deeper in the analysis: what were the organizational patterns associated with the roof successes and failures? Which arrangements can detect crucial errors and correct them, and which cannot? The answer to that question could affect all of architecture.

A cruel but pointed project would be a systematic study of the failings of the buildings that house university architecture departments. Invariably designed and built with great fanfare, as a class they are perhaps the most loathed of all academic buildings. From Paul Rudolph’s infamously brutalist Art and Architecture Building at Yale to the harsh Wurster Hall at Berkeley, the buildings are exciting and unworkable. Are they unworkable because they are exciting? Do these theory-based “statements” and sculptural experiments necessarily and always impede daily function? Also: what do the students learn from these buildings-to avoid the mistakes, or to imitate them? After the buildings got built and got noticed, and those are the man criteria of success for an architect as the profession stands today

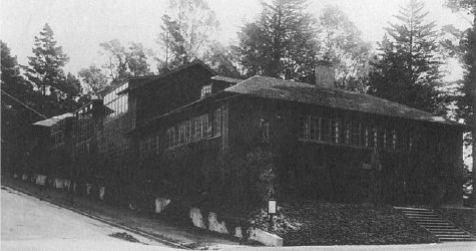

Bancroft Library. Neg. No. 16:D2. Reprinted from a book about “The Ark” Sally B. Woodbridge En Charette/On Deadline (Berkley: Graduate School Of Journalism, 1993).

ca 1922 - The original, hip-roofed part (right) of “The Ark” was designed in 1906 by the Architecture the chairman, John Galen Howard. Beach new addition retained the originals homeyness and its Berkeley Shingle style. The building grew around a courtyard, faced on one side by along, sunny corridor connecting all the studios, where teachers felt comfortable sticking their head in what was up. Built originally as a temporary building, it now is on the National Register of Historic Places

25 August 1993. Brand.

1993 Completed in 1964, the School of Environmental Design was designed by Joseph Esherick, Venom DeMars, and Donald Olsen to serve 1400 people (60 faculty) Professor Van der Ryn recalls, William Wurster commissioned three faculty with entirely different philosophies to design the building. He thought it would be interesting to put them together and see what happened. What happened was an incredible and a building that I don’t think is even as good as the most mediocre work of any one of them. There are very few seminar rooms. The architecture studios are completely chaotic Students walk back where they’ve set up and their desk is gone. The mechanical systems are ridiculous-in the summer in the south rooms the heat is going. and in the winter it’s off. Luckily the windows do open.

Drawings from Sally B. Woodbridge En Charette/On Deadline (Berkley: Graduate School Of Journalism, 1993).

Like a New England connected farm, The Ark grew around a south-facing courtyard, adding studios, an exhibit hall lecture hall, more studios, a pergola converted to a corridor, and a library. In 1981 the School of Journalism took over the building. “As soon as we moved in,” they reported, we felt cohesion”.

THE LOVED AND THE UNLOVED. In 1964 the Architecture Department of the University of California, Berkeley, moved from an old building (above) to a new (right)-from one that had grown with the department for 58 years to one that was specially designed for it. The old one, known as “The Ark,” is described as “one of the most revered buildings on the campus.” As for the new one, Wurster Hall, “It’s a real brute of a building,” says architecture professor Sim Van der Ryn, who taught in both buildings. He explains, “I prefer a one-story responsive wood building to a ten-story extremely inflexible concrete one. When you go from a horizontal plan to a ver tical one, immediately you develop a kind of hierarchy, and there’s less communication. Sometimes I teach for a whole semester now and people say, ‘I thought you were on leave.’”

The field of architecture takes its counsel from two main sources-architecture schools and architecture magazines of which deliberately isolate themselves from the real sources of feedback on building performance-lawyers and developers. Architects don’t approve of lawyers or developers. They also diligently ignore facilities managers, the people most steeped in building function and malfunction. Frank Duffy told a conference facilities managers, “I as an architect find facilities management liberating because it introduces the dimensions of time and use into buildings. “27 Author Fred Stitt observes, “For years architects and engineers have largely overlooked an enormous potential source of design work… Facilities managers can give you long- term renovation and maintenance contracts on their buildings. Those contracts make you the ‘house design firm’ and lead you directly back to major new building projects in the future.”28 Such a long-term relationship is exactly the sort that William Seale lauded in 19th century French architects.

In 1990 the American Institute of Architects polled its members on what competencies they would most like to develop. Out of the dozens offered, the next-to-last was “Develop facilities management services. “29

Schools of architecture, in my limited experience, are wonderful and terrible. Wonderful because they foster the last great broad Renaissance-feeling profession, terrible because they do it so narrowly. They focus obsessively on visual skills such as rendering, models, plans, and photography. Sight substitutes for insight. The artistic emphasis discourages real intellectual inquiry, diverting instead into vapid stylistic analysis, and it shuts out the experience of non-artists such as engineers and real estate professionals.

Even riper for revolution than the schools are the architectural magazines. Any one of them could build circulation with a several year crusade against the scandals in their industry, taking the perspective of the aggrieved users of buildings. People cannot believe that something so obviously important and permanent as buildings can be designed so badly. Unchallenged practices persist for decades-sliding glass doors and floor-to-ceiling glass partitions that people smash their noses on; extensive south- a west-facing windows that become solar ovens; extensive ground- rooms designed symmetrically to be the same size as men’s floor windows that people invariably curtain for privacy; women’s rooms, when double the size and facilities are needed; and the innumerable sad, dry, leaf-filled courtyard fountains that looked so cheery on the renderings but were too much trouble maintain.

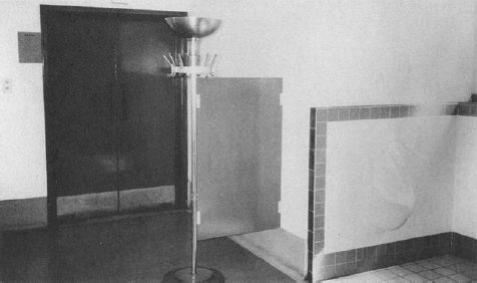

September 1990. Brand.

THE MEN’S ROOM of the Royal Institute of British Architects in London offered an unimpeded view of the urinals from the corridor when anyone went through the doors. A strategically-placed coat rack and modest panel corrected the error without bothering to conceal it. It’s an endearingly inexpensive fix, no doubt instructive to young architects.

Architecture magazines could be the monthly avenue of feedback for the profession on what works and doesn’t work. Instead are the monthly barrier. What architects are kept well abreast of are the things which have advertisers-new materials and new technology. That’s helpful in a world of fast-moving technology, but what is even more needed than simple description is sis of reliability, life-cycle behavior, environmental impact, user acceptance, compatibility with other materials, ease of disassembly-the sort of thing that Consumer Reports does for ordinary people.30

It would be nice to see architecture magazines invent an entertainingly journalistic form of post-occupancy evaluation of us buildings new and old. Let careers rise and fall on those criteria for a change. People learn quickest from other people’s mistakes, especially if the errors are assessed with compassion and humor. Prestigious design awards could be redirected. The American Institute of Architects’ 25-Year Award” is on the right track because it honors time, but it pays no attention to use, only to abiding stylistic influence. Much better is the Rudy Bruner Award, which rewards social effectiveness and requires the jury to visit the candidate buildings. We need to honor buildings that are loved rather than merely admired. Admiration is from a distance and brief, while love is up close and cumulative. New buildings should be judged not just for what they are, but for what they are capable of becoming. Old buildings should get credit for how they played their options.

The needed conversion is from architecture based on image to architecture based on process. Some architects see it coming. Herman Hertzberger, in Holland, writes, “The point is to arrive at an architecture that, when the users decide to put it to different uses than those originally envisaged by the architect, does not get upset and consequently lose its identity… Architecture should offer an incentive to its users to influence it wherever possible, not merely to reinforce its identity, but more especially to enhance and affirm the identity of its users.”31

Sir Richard Rogers affirms, “One of the things which we are searching for is a form of architecture which, unlike classical architecture, is not perfect and finite upon completion… We are looking for an architecture rather like some music and poetry which can actually be changed by the users, an architecture of improvisation.32

Frank Duffy hectors his profession: “The reason I hate these architectural fleshpots so much is because they represent an aesthetic of timelessness, which is sterile, If you think about what a building actually does as it is used through time-how it matures, how it takes the knocks, how it develops, and you realize that beauty resides in that process-then you have a different kind of architecture. What would an aesthetic based on the inevitability of transience actually look like?”

The conversion will be difficult because it is fundamental. The transition from image architecture to process architecture is a leap from the certainties of controllable things in space to the self organizing complexities of an endlessly raveling and unraveling skein of relationships over time. Buildings have lives of their own.

Buy the book here.33 and watch the TV series here.

-

Stewart Brand, The Media Lab (New York: Viking Penguin, 1987). ↩

-

The saga of the problem-filled creation of the building is told in Artists and Architects Collaborate: Designing the Wiesner Building (Cambridge: MIT Committee on the Visual Arts, 1985). ↩

-

C. Thomas Mitchell, Redefining Designing (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993), p.30 ↩

-

The best source on this history is Andrew Saint, The Image of the Architect (New Haven and London: Yale, 1983) See Recommended Bibliography ↩

-

Henry Glassie, “Folk Art,” in Material Culture Studies in America (Nashville, TN. Am Assoc for State and Local History, 1982) ed. Thomas J. Schlereth, p. 126.

A standard line among potters is: “If it holds water, it’s craft. If it leaks it’s art.” ↩

-

Long Life, loose fit, low energy was an all-too-briefly popular mantra introduced in 1972 by British architect Alex Gordon. The energy crisis of 1973 proved him prescient ↩

-

Robert Venturi, et al., Learning from las Vegas : The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form (Cambridge MIT Press, 19721977 ↩

-

Michael Benedikt, For An Architecture of Reality (New York: Lumen, 1987), p. 14. ↩

-

Francis Duffy, The Charging Workplace (London: Phaidon, 1992) p.232. ↩

-

Franklin Becker, The Total Workplace (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1990), p. 25, 125. (See Recommended Bibliography) Also: Patrick Hannay, “A Tale of Two Architectures,” Architects’ Journal (29 Oct. 1986), pp. 29-40. Also: Mira Bar Hillel, Offices That Are Just Too Clever By Half, London Sunday Telegraph (7 Oct. 1990). ↩

-

Judith Donahue, Fixing Falling Water Flaws, Architecture (Nov., 1989), p. 100. Someone should have replied to Wright, “That’s how you can tell it’s a failure ↩

-

Frank Lloyd Wright: Writings and Buildings, Edgar Kaufmann and Ben Raeburn, ca. (New York: Meridian, 1960), p. 90. ↩

-

Above title, p. 289. ↩

-

George Oakes in Lloyd Kahn’s Refried Domes, p. 1, (1989; $7 postpaid from Publications, P.O. Box 279, Bolinas, CA 94924). Lloyd Kahn’s enthusiastic Earth Domebook II (1972), sold 175,000 copies. By the late 1970s, his grim experience domes converted him from a proponent and builder to a critic. He tore down dome home and replaced it with a conventional structure. ↩

-

Still in print. Orson Fowler, The Octagon House: A Home for All (New York: Dover 1853, 1973) ↩

-

Refried Domes, p. 7. ↩

-

A bracing read for American and European professionals is: Sidney Levy, Japanese construction (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. 1990).

The Economist reports, “In Japan common for the architect’s drawings to be altered radically on the building site. All such sites have field offices, known as genba, where architects and builders work together. This helps them to collaborate on the unforeseen problem of detail, the sudden glitch.” That Certain Japanese Lightness,” The Economist (22 Aug. 1992), p. 75. ↩

-

Joel Garreau, Edge City (New York: Doubleday, 1991), p. 326. See Recommended Bibliography ↩

-

Robert Venturi et al. Learning From Las Vegas (Cambridge: MIT, 1972), p. 106. Quoted in C. Thomas Mitchell, Redefining Designing (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993).p. ↩

-

Deborah Devonshire, The Estate (London: Macmillan, 1990), p. 149. ↩

-

Sim Van der Ryn and Murray Silverstein, Dorms at Berkeley (Berkeley: UC Center for Planning and Research, 1967). ↩

-

Elena Marcheso Moreno, “The Many Uses of Post Occupancy Evaluation,” Architecture (Apr. 1989), pp. 119-121. ↩

-

The Occupier’s View: Business Space in the ’90s. This 1990 study is the best public, general-purpose POE I have seen, rare and priceless (if pricy). Done by a surveyors (real estate) firm called Vail Williams, it costs $50 from Vail Williams, 43 High Street, Fareham, Hampshire, PO16 7BQ. England.34 See Recommended Bibliography ↩

-

Preiser, Rabinowitz, and White, Post-Occupancy Evaluation (New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1988), p. 28. Architects are increasingly regarded as out-of-it tyrants. “Large organisations are now convinced of [the] link between adaptability and survival, often preferring to commission new buildings with a project manager rather than an architect in charge. In the traditional, vertical design team, the services and structural engineers have no real chance of equality with the generalist architect. The operational stakes are now knowledge by the more sophisticated companies to be too high to allow non-specialists in these areas to take overall control.” Steelcase Stafor. The Responsive Office (Streatley-on-Thames: Polymath, 1990), p. 73. ↩

-

Judith Blau, Architects and Firms (Cambridge: MIT, 1984), cited in Dana Cuff, “Fragmented Dreams, Flexible Practices,” Architecture (May 1992), p. 80. ↩

-

B.J. Novitski, “Roofing Systems Software, Architecture (Feb. 1992), p. 102. ↩

-

Francis Duffy, “Measuring Building Performance,” Facilities (May 1990), p. 17. ↩

-

Fred Stitt, Designing Buildings That Work (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985). p. 107 ↩

-

The very least preferred was. “Apply knowledge of seismic construction.” The next-to last pursued competency was, “Perform post-occupancy evaluations.” Joseph Bilello and Cynthia Woodward, “Results of AIA Learning Survey.” Architecture (Sept. 1992), p. 100. The magazine had no comment on these findings. ↩

-

An impressive example of this kind of reporting is Environmental Building News (bimonthly. $60/year from: EBN, RRI Box 161, Brattleboro VT 05301). ↩

-

Hermaman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture (Rotterdam: Utgeverij 010, 1991), p. 148. ↩

-

Sir Richard Rogers, “The Artist and the Scientist,” in Bridging the Gap (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991), p. 146. ↩

-

There is a PDF here, but it’s of a different edition to the one I OCR’d for this. There’s also an epub here if you want to read it on a Kindle. The book is very nice, if a bit odd to read from (landscape pages), so you should buy it. ↩

-

I’ve contacted Vail Williams to see if they still have copies of this report, but in the meantime, here’s what The Times said at the time: (The text is from an OCR archive, and so it quite mangled.)

THE TIMES WEDNESDAY JUNE 6 1990: COMMERCIAL PROPERTY

By Christopher Warman

Building up another set of problems

The developer, the architect and the agent may be satisfied with the commercial property they have brought to the market, but often the final link in the chain — the occupier — is not fully content, according to a survey carried out by the agents Vail Williams.

In the survey, 58 companies housed in modern business space were interviewed, and after seeing the results, John Vail, joint senior partner, concludes: “We believe it provides some fascinating, controversial, yet valuable insights to which we must respond if we are to service effectively this ever more sophisticated market place.”

Vail Williams believes that its report, The Occupier’s View - Business Space in the “90s, is the first in-depth, post-occupancy evaluation of its kind. If so, the occupants have given freely of their opinions.

Most occupiers were satisfied with the external appearance of their buildings and the landscaping, “although the glass boxes so beloved for so long are less favoured today than the traditional brick and pitched -roof construction”.

Most of the concerns covered the interior of the buildings and their practicality, and as one firm put it: “The primary interest to be aesthetic rather than

Companies are often unhappy with their shiny new premises practicality. It is no good if it looks nice and doesn’t work.”

Another comment about architects highlights foe need for contact once the building is occupied. “They never come back to leant either what is good or bad.** Architects are criticized, too, for not listening to foe tenant and little effort to understand

developers escape criticism. One interviewee described them as “ostriches with their heads firmly buried in the santF, reluctant to enter a dialogue with occupiers. Agents were also criticized, particularly for their lad: of knowledge of the buildings they were marketing.

In design, tenants were most dissatisfied with cleaning and maintenance and budding services, some of which were minor matters but a great source of irritation.

Examining the complaints, Vail Williams maims three recommendations to try to ensure that foe mistakes of foe 1980s are not repeated. The main one is that buildings larger than 25JJOO sq ft should be left to a shell-and-core finish. The practice of providing fully fitted buildings, seen to be a marketing necessity, leads the eventual occupier to carry out an expensive refitting or to settle for a compromise. Of the interviewees, 79 per cent preferred-shell and core buddings.

A comprehensive check list, covering the of design features should be compiled by the development team, Vail Williams says, and rigorously followed, and. the measurement of buildings should be standard. Many companies looking for premises do not understand the difference between gross and net internal space, the report states. It recoxn-

gross internal figures for all busk ness space buildings and that net internal figures should be quoted purely for comparative reasons.

The report concludes that occupiers would welcome foe opportunity to explain their needs, particularly the way in which they use their space, yet the development industry to date “just does not seem to have taken any real interest, with one or two rare and notable exceptions**.

Nick Wakeley, head of research at Vail Williams, says: “Without a feedback loop from customer to supplier, errors and oversights will simply recur from one generation of buildings to another. The needs of the occupier are paramount and they are not being satisfied. Only through a post-occupancy evaluation of buildings can we develop a clearer understanding of what they want.” ↩